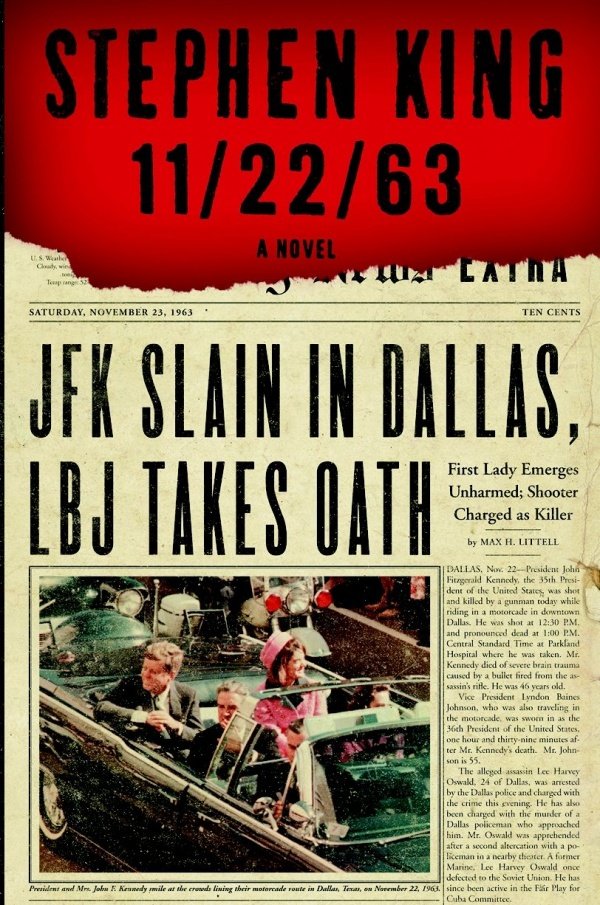

Change the past: A review of Stephen King's "11/22/63"

A review of "11/22/63"

A review of "11/22/63"

Time travel is tricky. Problem number one: You probably don't have a time machine parked in your garage. Not yet, anyway.

But let's assume you do. You rev up your metallic silver Chronos 1000. But the future doesn't interest you. You're tempted to visit the past. Because who can resist mucking with history? Nobody.

Depending on which rules of time travel are in effect, the outcome of your meddling will differ. If history is fixed and unchangeable, nothing happens. If alternate parallel histories can coexist, you may visit 1912, warn the Titanic's captain to watch for icebergs, and save those doomed passengers. Unfortunately, they'll still perish in the original timeline. Not a terribly satisfying save-the-day scenario.

Or as Stephen King posits in his new science fiction thriller "11/22/63," there's theory number three: history is flexible. Your backward travels can warp the course of future events (as long as you don't create a paradox, like challenging yourself to a duel).

King wonders what would happen if you time-trekked back to 1963 and killed the assassin before he got to President Kennedy. Would changing that watershed moment have prevented the country’s military escalation in Vietnam, saved the lives of RFK and MLK, yadda, yadda yadda -- in short, prevented many of the latter half of the 20th century’s ills? Those questions frame the basic premise of King’s book.

Assassinations and rifts in the space-time continuum are not foreign concepts to America’s King of Pulp. In “The Dark Tower’’ series, magical doors link far-flung worlds. In “The Dead Zone,’’ the clairvoyant protagonist shoots the president to avert nuclear Armageddon. Here, to kick-start the plot, King builds a wormhole in the pantry of a diner in Lisbon Falls, Maine. Like an express train, the time tunnel connects two destinations in history: the present and Sept. 9, 1958. Al, the diner’s tetchy proprietor, has been there and back a few times, mainly to buy hamburger at 54 cents a pound so he might sell 2011 burgers for $1.19. “Turns out I’m no longer tied to the economy the way other people are,’’ he jokes. Then Al finds a higher cause: Surveil Lee Harvey Oswald, determine whether he is the lone gunman, and take him out.

King ups the stakes with his own twists. Every visit back in time, no mat ter how long, takes only two minutes in the present. While in the past, travelers age normally. To accomplish his mission Al would need to go back to 1958 and stay five years. But his lung cancer would prevent him from lasting until 1963. The solution? Recruit Jake Epping, a 35-year-old high school English teacher, divorced, no children, and our first-person narrator. Jake takes up the quest, chucking his cellphone - “Keeping it would be like walking around with an unexploded bomb’’ - to live full time 53 years ago, pseudonymously as George Amberson. Jake/George soon discovers history is resistant to change, in direct proportion to the size of the event he wants to bend. “Obdurate’’ is the refrain. But the past can also be redeemed. If Jake kills Oswald and returns to 2011 to find the world ain’t better, a journey back restores history. “Every trip is the first trip,’’ Al says. “Because every trip down the rabbit-hole’s a reset.’’

The historical novel is already a well-established literary time machine, and King, who was 16 when JFK was shot, has done his homework, setting his characters on plausible collision courses with actual people and lovingly populating his “Land of Ago’’ with period details: drive-ins, pop songs, pep clubs, and finned convertibles. King balances his nostalgia on the cusp of tumult, just before this more naive world would be homogenized by television and strip malls and its smaller mind would wake up to racial injustice and military quagmire. As the author said in a recent interview, “11/22/63 was our 9/11.’’

No overt evil or supernatural presence haunts the novel, but buildings like an abandoned factory in Derry (a fictional Maine town readers of “It’’ and “Bag of Bones’’ will recognize) feel menacing. The Texas School Book Depository, where Oswald erects his sniper perch, emanates red-hot historical radiation. “The past harmonizes with itself,’’ Jake says, feeling more wraithlike than human. All through “11/22/63,’’ coincidences - often violent ones - ripple and accrue the longer Jake hangs around.

King’s thriller is full of suspense, and yes, you’ll want to know whether Jake gets to Dealey Plaza in time to stop the assassin’s bullet. If you’re not turned on by JFK conspiracy theories, the painstaking details of Oswald’s every move might feel tedious. You’ll also want to overlook how resourceful King makes his teacher, who conveniently knows about guns and surveillance techniques, and how to smooth-talk FBI agents.

Yet, uncharacteristic for Stephen King, a love story overshadows Jake’s creepy rendezvous with destiny. While in singular pursuit of Oswald, our hero settles in small-town Jodie, Texas, where he becomes a schoolteacher, falls for a clumsy librarian named Sadie, and starts accumulating his own cause-and-butterfly-effect. Helping a football player blossom into an actor, Jake/George finally sheds his ghostly trail - “It was when I stopped living in the past and just started living.’’ “11/22/63’’ ends up shining brightest as a metaphorical journey about “stupidity . . . and missed chances,’’ the perils of memory and regret, and the fantasy of starting over. To redeem America’s wounded psyche, Jake may or may not save the president. To redeem himself, he merely has to decide where to be present, and how to be present, in time.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of “Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms.’’ He can be reached at www.ethangilsdorf.com.

[this first appeared in the Boston Globe]

To reprint this or one of Ethan Gilsdorf's other articles, contact sales@featurewell.com or visit http://www.featurewell.com

When literary authors slum in genre

There’s a curious phenomenon happening out there in LiteraryLand: The territory of genre fiction is being invaded by the literary camp.

There’s a curious phenomenon happening out there in LiteraryLand: The territory of genre fiction is being invaded by the literary camp.

While it could be argued that literary writers have always borrowed from fantasy, science fiction and horror, even stolen genre's best ideas, I think there's a new and significant shift happening in the past few years.

Take Justin Cronin, writer of respectable stories, who recently leaped the chasm to the dystopian, undead-ridden realm of Twilight. With The Passage, his post-apocalyptic, doorstopper of a saga, the author enters a new universe, seemingly snubbing his former life writing “serious books” like Mary and O’Neil and The Summer Guest, which won prizes like Pen/Hemingway Award, the Whiting Writer’s Award and the Stephen Crane Prize. Both books of fiction situate themselves solidly in the camp of literary fiction. They’re set on the planet Earth we know and love. Not so with The Passage, in which mutant vampire-like creatures ravage a post-apocalyptic U.S. of A. Think Cormac McCarthy’s The Road crossed with the movie The Road Warrior, with the psychological tonnage of John Fowles’ The Magus and the “huh?” ofThe Matrix.

Now comes Ricky Moody, whose ironic novels like The Ice Storm andPurple America were solidly in the literary camp, telling us about life in a more-or-less recognizable world. His latest novel, The Four Fingers of Death, is a big departure, blending a B-movie classic with a dark future world. The plot: A doomed U.S. space mission to Mars and a subsequent accidental release of deadly bacteria picked up on the Red Planet results in that astronaut’s severed arm surviving re-entry to earth, and reanimating to embark on a wanton rampage of strangulation.

And there’s probably other examples I’m forgetting at the moment.

So what’s all this forsaking of one’s literary pedigree about?

It began with the flipside of this equation. It used to be that genre writers had to claw their way up the ivory tower in order to be recognized by the literary tastemakers. Clearly, that’s shifted, as more and more fantasy, science fiction, and horror writers have been accepted by the mainstream and given their overdue lit cred. It’s been a hard row to hoe. J.R.R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Philip Pullman and others helped blaze the trail to acceptance. Now these authors have been largely accepted into the canon. You can take university courses on fantasy literature and write dissertations on the homoerotic subtext simmering between Frodo and Sam. A whole generation, now of age and in college, grew up reading (or having read to them) the entire oeuvre of Harry Potter. That’s a sea change in the way fantasy will be seen in the future—not as some freaky subculture, but as widespread mass culture.

Yes, Margaret Atwood and Doris Lessing have delved into genre, although their works (A Handmaid's Tale, for example) was always taken as highbrow. Perhaps a better example: Stephen King, considered a hack horror writer for years who began publishing in the New Yorker in 1990. One wonders why the New Yorker finally caved and let him in the doors --- is this an implicit acknowledgement of his popularity? Or had King's writing gotten better. In any case, it's was a shocker when he began racking up impressive literary kudos, like in 2003 when the National Book Awards handed over its annual medal for distinguished contribution to American letters to King. Recently in May, the Los Angeles Public Library gave its Literary Award for his monstrous contribution to literature.

Now, as muggles and Mordor have entered the popular lexicon, the glitterati of literary fiction find themselves “slumming” in the darker, fouler waters of genre. (One reason: It’s probably more fun to write.) But in the end, I think it’s all about call and response. Readers want richer, more complex and more imaginative and immersive stories. Writers want an audience, and that audience increasingly reads genre. Each side—literary and genre—leeches off the other. The two camps have more or less met in the middle.

One wonders who’s going to delve into the dark waters next—Philip Roth? Salman Rushdie? Toni Morrison? Actually, it turns they already (sort of) have --- Roth explores alternative history in The Plot Against America;

Rushdie's "Magical Realism," of Midnight's Children, in which children have superpowers. You might even argue that Morrison's Beloved is a ghost story.

[thanks to readers at Tor.com, where this post originally appeared, for catching some errors and helping me revise this into a better essay]

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, which comes out in paperback in September. Contact him through his website,www.ethangilsdorf.com