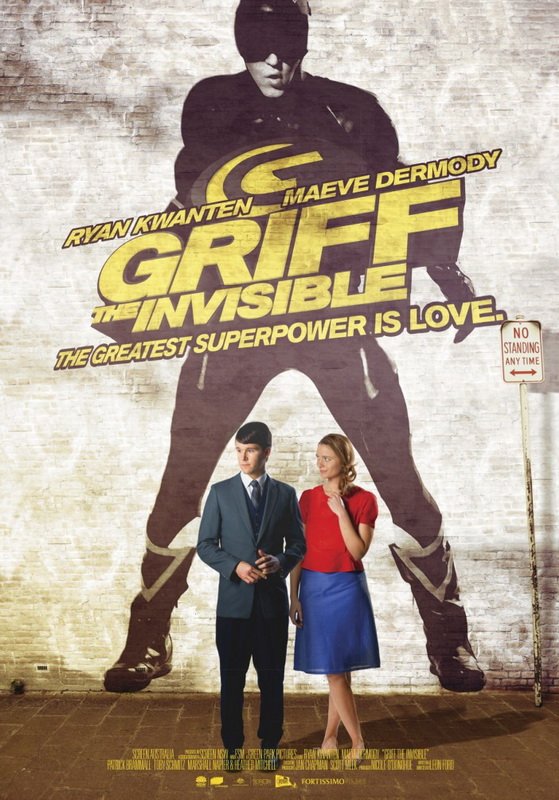

MOVIE REVIEW: "Griff the Invisible" joins the growing ranks of DIY superheroes

[This originally appeared in the Boston Globe]

[This originally appeared in the Boston Globe]

Between the recent spate of spandex-stretching franchises clogging the screen - lanterns, hornets, Norsemen, captains - and the trend of movies about everyday people with save-the-day complexes, it’s beginning to look like we’re a superhero-obsessed culture.

“Griff the Invisible,’’ posits itself firmly in this latter, DIY tradition, a budding genre already well trampled by “Kick-Ass,’’ “Super,’’ “Defendor,’’ and “Scott Pilgrim vs. the World.’’ In these movies, average Jacks and Jills, sans superpowers to speak of, craft their own costumes to fight crime. These vigilantes may or may not be crazy.

Here, Australian writer-director Leon Ford, making his feature debut, casts Ryan Kwanten (HBO’s “True Blood’’) as the introverted Griff, a browbeaten office worker who wears a yellow raincoat to “disappear’’ during the day, and dons a black, Batman-like outfit to prowl Sydney at night. He’s tricked out his apartment with surveillance equipment and a hot line to the police commissioner.

As Griff explains to his protective older brother (Patrick Brammall), who begs him to end his dangerous cape crusading, “Sorry, Tim, I made a promise to rid this city of evil. It’s not a choice. It’s a responsibility.’’

His sense of duty may not be a choice for another reason: Griff is mentally ill. Or is he? That’s the question “Griff the Invisible’’ dangles over the viewer like a thought balloon - what measure of fantasy and reality balances the world of this magically-thinking nerd?

The ante is upped when a woman Tim is dating, Melody (Maeve Dermody), herself a dreamer in a different way, falls for Griff. Her geekery involves a belief in her ability to walk through walls. She spouts statistics and bumps her head a lot.

Griff’s “invisibility’’ and alter-ego games serve as metaphors. The bad guys are slaves to social norms, Ford is saying, “for seeing the world one way,’’ while a minority are heroes for refusing to grow up and keeping their freak on. Cute idea, if not terribly original.

Yet “Griff the Invisible’’ is really a rom-com, and thus depends on sparks flying between the two lovers. Yes, as the romance blossoms, our hero is vindicated when Melody accepts his quirks, even enables his fantasy life. But the touches of magical realism begin to feel gimmicky. By the final frame, this romance never feels real enough.

Ethan Gilsdorf can be reached at www.ethangilsdorf.com. ![]()

Guillermo Del Toro: The Interview, Part II

[this originally appeared on wired.com's Geek Dad]

Here’s Part II of my conversation with Guillermo del Toro, director of Cronos, The Devil’s Backbone, Mimic, Pan’s Labyrinth, Blade II, and the two Hellboy films. [Read Part I of the interview here.]

Del Toro, a former special effects makeup designer, has his own aesthetic: melding of the man-made past — the handcrafted technology of wood, leather, brass, iron — and the organic world of slugs, bugs, and tentacles. He has a fascination with mechanical gadgets, the colors amber and steel blue, and body parts embalmed in jars. You might say he’s invented his own genre: not the clockwork and piston of “steampunk,”’ but more gut-and-gears, something I call “steam-gunk.” (For a peek into del Toro’s sketchbooks, see this previous wired.com link to a fascinating video).

His latest film is one he didn’t direct, but he did co-write and produce: Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, a throwback to old fashioned haunted house films, starring Guy Pearce, Katie Holmes and Bailee Madison. The family moves into an old mansion and the daughter discovers an ancient evil inhabiting the basement’s ash pit. Scary stuff ensues.

When not prepping for his next stint behind the camera (the giant robot battle film Pacific Rim), Del Toro told me that he’s preparing for the rapidly-approaching age of “transmedia” and “multi-platform world creation,” when audiences will read books, play games, watch movies and webisodes, all set in the same world. To that end, he’s been working in fiction (The Strain is his post-apocalyptic, vampires-in-NYC trilogy) and a Lovecraftian horror video game.

But whatever the media, del Toro’s goal, it seems to me, is never to gratuitously freak us out. Rather, he just wants to touch us. Or as he puts it, “to make beautiful and moving images, and beautiful and moving stories within the genre.”

One of the homunculi from "Don't Be Afraid of the Dark"Ethan Gilsdorf: To me, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark was interesting because typically in a film set in a haunted house, the horror that has happened in the past gets reflected in ghosts, or in things that are more spiritual. In this movie, these little creatures, the homunculi, are really a different kind of manifestation of that curse.

One of the homunculi from "Don't Be Afraid of the Dark"Ethan Gilsdorf: To me, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark was interesting because typically in a film set in a haunted house, the horror that has happened in the past gets reflected in ghosts, or in things that are more spiritual. In this movie, these little creatures, the homunculi, are really a different kind of manifestation of that curse.

Guillermo Del Toro: The idea in the movie is that these creatures presented predate even the time when the land was colonized. There is a small reference in the movie about how in the colonies they built a mill and it sank into the caves. So the caves in that area have lodged these creatures which are very old. They predate man setting foot in there.

EG: Do you have a sense of why horror movies, especially those with supernatural elements, remain critically underappreciated? I suspect it’s related to the same way that other kinds of genre movies are received, but in some way horror has had less of a critical reevaluation, unlike science fiction or fantasy which seem to be genres people don’t pass judgment on as quickly as they used to. With horror or movies of the supernatural, there is still a stigma in the critical community. Any thoughts on why that is the case?

GDT: The movies that depend on an emotional reaction — being comedy, melodrama, horror — because precisely they are trying to elicit an emotion from the audience, they become almost a challenge to audiences and critics. It’s very hard for the critical audience to admit they got emotional in a movie. It’s sort of admitting defeat. A movie that tries to provoke on a purely intellectual level is always going to be met [more favorably] … Those who claim [they are] stimulated intellectually by that movie almost by proxy are defining themselves as intelligent. They are defining themselves as affected on a higher level. Movies that depend on an emotional reaction are oftentimes almost a dual situation: you go to a comedy as a critic or an audience member, almost saying, “Come on, do your worst. Make me laugh.”

And the same in horror movies. Being scared is often regarded as a childish or immature emotion. It’s very hard to establish that you are affected by [this kind of] movie without admitting that you love stuff that is more challenging.

Historically, science fiction requires more production value than horror. And other genres like comedy or melodrama don’t depend on the budget. There’s never been a categorization like a “B-[movie] melodrama” or whatever. Horror movies [are] a very quick and cheap entryway into the mainstream, in a way. They are very numerous and very visually objectionable, if you will, and very visually low budget and industry-defying. They are qualified as cheap products to cash in. That is true of many of the movies of the genre. But not all of the movies of the genre.

EG: What are some of the movies that you’ve seen that have affected you? I know the original version of this movie, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, you said was one of the scariest pieces of television that you’ve seen. What are some of the films, either recently or ones that go back decades, that you would say have frightened or disturbed you the most?

GDT: The list is the usual. The Shining, Alien, The Innocents, The Haunting, Jaws, The Uninvited with Ray Milland, The Dead of Night (the British movie), The Curse of the Demon … But recently I was very affected by a Korean movie that is very, very extreme called I Saw the Devil. I was very, very affected by it. It’s a very in your face, a broad, brutal, movie, but highly effective.

EG: How do you see your own work having grown or evolved over the years since you first got started as a filmmaker? How do you think you’ve changed?

GDT: Well, I think that technically I’ve become more proficient at certain things, but in terms of artistic intention, I think from he get-go, from Cronos on, I’ve always tried very hard in my own way to make beautiful and moving images, and beautiful and moving stories within the genre. That has been basically unwavering in my intention in creating things. Even in the more commercial movies like the two Hellboys, I tried very hard to fabricate beautiful images, and beautiful moments. Even in a movie as hardcore as Blade II I tried very hard [to make] a beautiful image here and there.

EG: Do you ever long to do something that’s fairly conventional, in terms of just a straight up drama or straight up comedy or something that doesn’t necessary include these more fantastical, supernatural or pulpy elements?

GDT: Not really. [Laughs.] I don’t think it’s in my DNA. I really think I was born to exist in the genre. I adore it. I embrace it. I enshrine it. I don’t look upon it or frown upon it in a way that a lot of directors do. A lot of directors make a horror movie as a steppingstone. For me, it’s not a steppingstone, it’s a cathedral.

EG: Do you feel like you have a particular lesson that you would like a young filmmaker or a beginning filmmaker, or for that matter a beginning writer, to take away from your work? Is there something that you hope an astute student would be able to appreciate of what you’re doing?

"Don't Be Afraid of the Dark": Dinner at the haunted manor, with Guy Pearce, Katie Holmes and Bailee Madison (Courtesy of FilmDistrict Distribution) GDT: No, I’m not trying to teach anyone anything. I think that’s a waste of time. I do hope that people who like [one of my movies] like it for the right reason. That they like it because they see how many of the moments in the movies run counter to what they are just supposed to do. The Devil’s Backbone’s ghost, I tried to make him more moving than scary. I tried to make him pitiful and beautiful. I tried to make the vampire sympathetic in Cronos. I tried to make the real world far more brutal in a way than the world of horrors that the girl experiences in Pan’s Labyrinth. And so forth. But they are not lessons by any means. They are just strands of my work that I hope that the people who like it notice.

"Don't Be Afraid of the Dark": Dinner at the haunted manor, with Guy Pearce, Katie Holmes and Bailee Madison (Courtesy of FilmDistrict Distribution) GDT: No, I’m not trying to teach anyone anything. I think that’s a waste of time. I do hope that people who like [one of my movies] like it for the right reason. That they like it because they see how many of the moments in the movies run counter to what they are just supposed to do. The Devil’s Backbone’s ghost, I tried to make him more moving than scary. I tried to make him pitiful and beautiful. I tried to make the vampire sympathetic in Cronos. I tried to make the real world far more brutal in a way than the world of horrors that the girl experiences in Pan’s Labyrinth. And so forth. But they are not lessons by any means. They are just strands of my work that I hope that the people who like it notice.

EG: Are you at liberty to talk about The Hobbit and share any thoughts about what is going on? Are you in touch with Peter Jackson and what’s going on down there in New Zealand?

GDT: We stay in touch. I said what I had to say. I really love having had the experience. Now it’s in Peter’s hands and I’m actually waiting for it to come out and I’ll be the first in line. Other than what I had to say, that there’s nothing else to add.

EG: Give me some thoughts on your field and the direction you think filmmaking is going to be headed. Whether this relates to the kinds of stories we’re going to be absorbing, the kinds of narratives, like filmmakers collaborating with game designers, or other changes.

GDT: I’m a firm believer that the narrative form, the storytelling form, for big genre stories, will very rapidly invade into transmedia, in multi-platform world creation, in the next ten years, when we’re going to have the movies, the video games, the storyline, the TV series or webisodes and this and that, all coming at us consecutively if not simultaneously to give the audience a real sense of a world creation. I’m not talking about [every film] — there will be all kinds of films always — just in the genre filmmaking I expect it will be changing. I’m very interested and very actively training myself by designing and directing a video game. I’ve been working on it for the last year and I still have three more years to go to develop the video game. … So by the end of the four years I will have had a bit of a tenure in video game making.

EG: Is that game going to be related to a film you are working on, or is it independent?

GDT: No, this is just my apprenticeship into the gaming world. And my experience has been a very beautiful and productive one. It’s with a company called THQ and it’s game called “inSANE.’’

EG: I see that we are out of time.

GDT: I want to thank you again for this.

EG: Thank you very much. Guillermo, it’s been a pleasure speaking with you.

Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark opens Friday, August 26.

[Note: Portions of this interview originally appeared in a different form in an article for the Boston Sunday Globe]

Horror story: With “Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark,” Guillermo del Toro keeps infusing horror with “beautiful and moving images”

by Ethan Gilsdorf

[originally appeared in the Boston Globe, Sunday Aug 21, 2011]

scene from del Toro's "Pan's Labyrinth"

scene from del Toro's "Pan's Labyrinth"

In director Guillermo del Toro’s estimation, most horror movies are cheap products to cash in, a quick and dirty way for studios to make a buck. Originality and artistry are discouraged.

“Few filmmakers,’’ del Toro said, “approach horror with the desire to create something either of substance or something beautiful or powerful. Most of the people just try to get a [big opening] weekend and DVD sales.’’

Del Toro, the man behind personal, vision-driven projects like “Cronos,’’ “The Devil’s Backbone,’’ and “Pan’s Labyrinth,’’ as well as the commercial successes “Blade II,’’ and two “Hellboy’’ films, has never seen horror as a temporary career move.

“I really think I was born to exist in the genre,’’ the quick-witted, outspoken Mexican filmmaker said in a telephone interview from New York City. “I adore it. I embrace it. I enshrine it. I don’t look upon it or frown upon it in a way that a lot of directors do. For me, it’s not a stepping stone, it’s a cathedral.’’

To make other kinds of film - comedy, drama - well . . . “I don’t think it’s in my DNA.’’

The latest spawn from del Toro’s imaginarium is “Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark,’’ a throwback to haunted house films of yore. Though he only co-wrote and produced the film - the director is newcomer Troy Nixey - “Don’t Be Afraid’’ (opening Friday) is still glazed with many familiar del Toro tropes: a dark prologue; the weight of ancient, historical forces; subterranean dungeons and mazes; and a hidden world of fantasy.

The original production was a 1973 ABC made-for-TV movie about a young couple in an abusive relationship who inherit an old mansion. Del Toro has claimed that, for his generation (he was 9 at the time), “Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark’’ was “the scariest TV movie we ever saw.’’

In 1998, del Toro began co-writing his version with Matthew Robbins, switching the focus to the couple’s daughter. Realizing the plot was too similar to “Pan’s Labyrinth,’’ he put the project on hold. “A young girl arriving at a foreign place, to an old mansion, discovering creatures underground,’’ del Toro said. “I didn’t want to repeat.’’

The film remained on the back burner of del Toro’s mind for more than a decade, but he kept pursuing it, finally beginning production two years ago. Shot in Australia, “Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark’’ is set in present day Rhode Island. We assume it’s Newport, given the lavish mansion an architect (Guy Pearce) and his interior-designer girlfriend (Katie Holmes) have renovated and moved into. The architect’s introverted daughter, Sally (Bailee Madison from “Bridge to Terabithia’’), reluctantly joins them.

The film traffics in another frequent del Toro theme: fantasy as escape from conflict. In “Pan’s Labyrinth,’’ against the backdrop of Fascist-era Spain, a girl suffers under a totalitarian father. While “Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark’’ isn’t set during wartime, Sally feels besieged by her parents’ divorce. Ignored by the adult world, she hears whispers from the basement. Her parents don’t believe the mischievous, rat-like homunculi that pour from the house’s innards truly exist. This is another classic del Toro thread: It’s the lonely, abandoned child who finds the secret doorway to the spirit and fairy world.

“I decided to turn it into a sort of very dark fairy tale,’’ del Toro said, “that taps into universal fears, the invasion of the most intimate spaces, the home, the bedroom, the bed. Little by little we show that these creatures can be anywhere at any time watching from the dark.’’

The de rigueur prologue concerns the previous owner of Blackwood Manor, a Victorian-era, Audubon-like illustrator and naturalist who became enslaved to an ancient evil inhabiting the basement’s ash pit. This opening back story (told in flashback) infuses the present with the horrifying past, but del Toro keeps his modern day protagonists in the dark. The gap between what the audience and the characters know is meant to provide the story’s urgency and tension.

“I think that no matter what culture you come from,’’ del Toro said, “the darkness and what lurks in it is an absolutely common fear. I think that ‘Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark’ taps into the most primal, almost universal, childhood fears. That’s what attracted me from the get-go to the idea of making this remake a complete re-telling of this story.’’

The former special effects makeup designer has his own aesthetic: a melding of the man-made past - the handcrafted technology of wood, leather, brass, iron - and the organic world of slugs, bugs, and tentacles. He has a fascination with mechanical gadgets, the colors amber and steel blue, and body parts embalmed in jars. You might say he’s invented his own genre: not the clockwork and piston of “steampunk,’’ but gut-and-gears “steam-gunk.’’

The goal is never to gratuitously freak us out. Rather, he aims to touch us. Of the boy ghost in “The Devil’s Backbone,’’ del Toro said he made him more “pitiful and beautiful’’ than scary. In “Cronos,’’ he depicted a sympathetic vampire. Even the crowd-pleasing action movies “Hellboy’’ and “Hellboy II’’ fit the del Toro ethos of flawed hero-outcasts; the protagonist, an orphaned demon rescued from Nazis, grows into a pathos-filled, cigar-chomping wiseacre, acutely aware of his oddball nature and still compelled to save the day. In “Pan’s Labyrinth,’’ del Toro created a “real world far more brutal . . . than the world of horrors that the girl experiences.’’ He has been unwavering, he insisted, in his intention “to make beautiful and moving images and beautiful and moving stories within the genre.’’

This time around, to realize those images and stories, he handpicked Nixey, a 39-year-old Canadian comic book illustrator for the Batman franchise and Neil Gaiman’s “Only the End of the World Again,’’ among other things. Nixey had made just one short film, “Latchkey’s Lament.’’ It captured del Toro’s attention.

“I saw that short. It’s really, really quite beautiful.’’ Watch it on YouTube, he said, “and you can see why he got the job.’’

Nixey still can’t believe that’s how he came to direct “Don’t Be Afraid,’’ but he was always clear that making his short would help cement his talent for filmmaking. “When I set out to make ‘Latchkey’s’ it was with the intention of proving that yes, OK, I can do this. I can think in terms of a movie,’’ said Nixey, a 17-year-veteran of the comics industry, speaking via telephone from New York. “But my first love had always been movies. This was me seeing if this was in fact what I was supposed to do.’’

Because “Don’t Be Afraid’’ was Nixey’s first feature film, del Toro was “very, very involved’’ in the production. “It’s the only movie I have produced where I have been almost 90 percent of the time on the set, every day,’’ del Toro said. “It was a big job to go from a short film . . . to something that intricate and that complicated.’’

Nixey agreed it was “a big leap’’ to direct a star-studded, multimillion-dollar film, but having what he called “my favorite filmmaker’’ and “a creative genius’’ nearby helped. “He [del Toro] said at the beginning, ‘I’m here when you need me and I’m not when you don’t.’ But I’m no dummy. He’s this amazingly talented, successful filmmaker with an imagination that I’ve never seen before. So, yeah, why wouldn’t I want to pick his brain when I had questions?’’

To see this Nixey-del Toro collaboration, audiences have had to be patient: The film was actually finished in 2010, but the protracted sale of Miramax delayed its release by months. Not only that, but del Toro fans have been wondering when their beloved master will direct again; he’s served as producer on this film and consultant or producer on more than a dozen other recent projects, but he hasn’t helmed a picture since 2008’s “Hellboy II: The Golden Army.’’

Del Toro has been bedeviled by bad luck and bad timing. He relocated to New Zealand to co-write and direct “The Hobbit,’’ but when that production repeatedly stalled, he backed out. Currently, Peter Jackson is filming the two-part adaptation of Tolkien’s fantasy book.

“We stay in touch,’’ del Toro said about his relationship with Jackson. “I said what I had to say. I really love having had the experience. Now it’s in Peter’s hands and I’m actually waiting for it to come out and I’ll be the first in line.’’

After “The Hobbit,’’ a $150-million, 3-D adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft’s novella “At the Mountains of Madness’’ was announced as del Toro’s next project, but studios balked at the price tag. It turns out del Toro’s next directorial effort will be a Japanese-style monsters versus robots film called “Pacific Rim,’’ which at this year’s Comic-Con he boasted would feature “the finest [expletive] monsters ever committed to screen.’’ Convinced that video games will continue to intersect with film and TV in “multi-platform world creation,’’ del Toro is also midway through “apprenticeship into the gaming world,’’ a multi-year project designing a Lovecraftian horror game called “inSANE.’’ He's also releasing book three in his horror novel trilogy "The Strain" (co-authored with Chuck Hogan); the final volume "The Night Eternal" comes out October 25, 2011.

Whatever the medium, del Toro keeps pushing the boundaries of this horror genre, which he said continues to be stigmatized because it depends on a visceral, not intellectual reaction.

“Being scared is often regarded as a childish or immature emotion,’’ del Toro said. “It’s very hard for the critical audience to admit they got emotional in a movie. It’s sort of admitting defeat.’’

If that’s the case, then may del Toro keep conquering us.

We're gonna need more holy water

Sure, the Crusades are morally reprehensible—but when it comes to battling evil, out come the holy water, sacred texts, and "in the name of the father" pronouncements.

a review of Season of the Witch

by Ethan Gilsdorf

What ever happened to the risky Nicolas Cage who took on meaty roles like Adapation? Or, at least, the one who played sincere characters like Ben Sanderson in Leaving Las Vegas? Or, for that matter, the comic and goofy Nic of Raising Arizona?

Rather, and sadly, the actor of late has imprisoned himself within a cage lackluster supernatural action vehicles like Ghost Rider, The Sorcerer's Apprentice, The Wicker Man, Next, and Knowing. In each, Cage possesses some awesome power, prognosticates some doomed secret, or stumbles across a malevolence force. Cue the time portals, fiery circles, demonic possessions, pagan rituals and creepy flash-forwards of knowledge mere mortals ought not to know.

In Season of the Witch, the hangdog-faced Cage (now with greasy, shoulder-length locks) confronts another paranormal conundrum, this time set in medieval Europe. Disenchanted by his time in the armed services, aka the Crusades, Behmen (Cage) deserts the war with his longtime fighting, boozing and whoring buddy Felson, played by the primitive-looking Ron Perlman (Hellboy, Hellboy II). "You call this glories? Murdering women and children?" is Behmen's anti-war epiphany moment, after he takes part in a massacre at the fortified city Smyrna. The two pals wander back home from the Holy War and are captured for going AWOL.

Meanwhile, Europe has been engulfed by the Black Plague. A dying Cardinal (Christopher Lee, ghastly enough without makeup but here unrecognizable behind icky prosthetics of festering boils and tumors) offers them clemency if they agree to transport a suspected witch, a girl played by newcomer Claire Foy, who is blamed for causing the plague. Get she to a monastery. The monks there will know what to do. Right.

Ergo, the quest commences.

An A team is assembled: our two heroes, a monk named Debelzaq (Stephen Campbell Moore, from The Bank Job), a stoic knight (Ulrich Thomsen), an elfin altar boy who craves adventure (Robert Sheehan, from Cherrybomb) and Hagamar, a convicted thief (Stephen Graham from "Boardwalk Empire") who is freed because he knows the way and because he can provide comic relief.

The journey takes the party through craggy mountains, barren plains and haunted forests. Much of the scenery is appropriately Dark Agedly forlorn. The film was shot in Hungary, Austria, Croatia, and that other European location known for its Old World charm, Shreveport, Louisiana, and the Eastern European film crew, who also handled much of the special effects, is chock with Istváns and Zoltáns.

Season of the Witch film borrows more than a few tricks from that other quest epic you may of heard of, The Lord of the Rings. The kinetic camera may as well have been controlled via remote control by Peter Jackson. It sweeps across CG landscapes melded with the real scenery and filtered with that bluish, gauzy light (likely added in post-production color grading), a look-and-feel we now associate with films set in days of yore. The score, composed by Icelander Atli Örvarsson ("Law and Order," "The Fourth Kind") includes more than its share of Howard Shore-esque brass fanfares and haunting choruses. And yes, one of the nasty forests they must cross, patrolled by wolf packs, is called ... not Mirkwood ... not Fangorn ... but Wormwood.

The Tolkien echoes don't end there. Behmen and Felson's friendly rivalry—"Whoever slays the most men, drinks for free"—recalls Legolas and Gimli's battlefield body-count contest, minus 99 percent of the chemistry. Likewise, Felson's "What madness is this?" line regurgitates Boromir's "What is this new devilry?" moment when the Fellowship first faces the Balrog in the Mines of Moria. To Perlmans's query, Cage replies: "This be a curse from hell."

No one attempts an English accent, which is probably for the best, for already Cage as heroic knight is hard to swallow. But director Dominic Sena (Gone in Sixty Seconds, Swordfish) makes no attempt to establish any sort of linguistic consistency. One moment, Hagamar, who speaks like he wandered off the set of "Jersey Shore," spouts lines like "Don't be deceived. She sees the weakness that lies in our hearts"; then he's all "Let's kill the bitch!" Likewise, early on our monk Debelzaq intones, "There is a whisper throughout the land, that the hour of our judgment is on us." Later, in the climactic battle, he exclaims, "We're gonna to need more holy water." Debelzaq may as well be channeling Roy "We're going to need a bigger boat" Scheider from Jaws.

Like in many action movies, the creaky script by Bragi Schut, Jr. (who wrote and directed the CBS sci-fi series "Threshold") tries to ride that knife edge: sober and serene so we'll buy the premise, yet giving the heroes a wide berth for wisecracks. Perhaps because Season of the Witch is meant to be taken as a period picture—OK, a supernatural thriller set in the 14th century—this familiar Hollywood cocktail of lofty prose and battlefield quips feels especially strained. Amazingly, Schut's screenplay won a major writing competition, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences's Nicholl Fellowship. Which does not instill much confidence in the Academy's ability to recognize good screenplays.

Schut's other problem is story. Much is made of whether the ragged girl is, in fact, a witch. Cage's character suspects she might be wrongly accused. You're not like the others—you're kind, the girl says. But the audience knows whether or not the innocent gal possesses supernatural powers long before the characters do; despite evidence that should alert our clueless heroes, they're unnecessarily dense. The unexpected wrinkle of exactly how the evil forces takes form partly redeems this plotting mishap, but not before the film's credibility has been battered.

A more serious shortcoming is the film's contradictory message. Early on, showing a rather a modern and enlightened perspective, Cage and Perlman defect from the Crusading army to protest the unjust and brutal wars. Killing soldiers and innocent women and children in the service of a Christian God is offensive, our heroes intuit. Yet Season of the Witch reveals its odd logic in the final reel. Sure, the Crusades are morally reprehensible—but when it comes to battling evil, out come the holy water, sacred texts, and "in the name of the father" pronouncements. Schut, our screenwriter, can't have it both ways—implicating the Church for atrocities that shoved Christianity down the throats of infidel Muslims, while suggesting that only Christian mojo can save the day.

Despite the drawbacks—the cumbersome script, the flat performances by Cage and Perlman—genre fans with their bars set low will find this junk food fun. The effects are decent. The production design's medieval grittiness is convincing. The scenery is moody and sometime staggering. (Attention Hungarian Tourist Board: begin your Season of the Witch movie location bus trips now.)

(Before I go, other gripe: Am I the only one dislikes that flickery, ever-so-slightly sped up combat photography so in fashion now? It's like you're viewing the fighting through an old-timey projector. Ridley Scott recently used this technique in Robin Hood. I find the jerkiness distracting.)

Ignoring Sena's cheap horror and suspense tricks, overall the action sequences are rousing, with plenty of mass-scale sword-clangings, torch-bearing through dark passages, and effortless beheadings. If you like your swords-and-sorcery mind-candy a campy blend of Tolkien and The Exorcist, and you don't mind a few groaners, Season of the Witch might, heroically, do the trick.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of the award-winning, travel memoir/pop culture investigation Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms (now in paperback). Follow his adventures at http://www.fantasyfreaksbook.com.

Picking up steam: Why is Boston the hub of steampunk?

Picking up steam

Mashing modern days with the Victorian age excites role players, artists, and other fans of steampunk

When Bruce and Melanie Rosenbaum bought a 1901 home in Sharon, they wanted to restore it top to bottom. And rather than force a modern interior design, they remodeled it with a Victorian twist.

In the kitchen, an antique cash register holds dog treats. A cast iron stove is retrofitted with a Miele cooktop and electric ovens. In the family room, a wooden mantle frames a sleek flat-screen TV, and hidden behind an enameled fireplace insert, salvaged from a Kansas City train station, glow LED lights from the home-entertainment system.

Unknowingly, the Rosenbaums had “steampunked’’ their home, that is, added anachronistic (and sometimes nonfunctioning) machinery like old gears, gauges, and other accoutrements that evoke the design principles of Victorian England and the Industrial Revolution.

“When we started this three years ago, we didn’t even know what steampunk was,’’ said Bruce, 48. “An acquaintance came through the house and said ‘You guys are steampunkers.’ I thought, ‘Wow, there’s a whole group out there that enjoys blending the old and new.’’

It’s not just the Rosenbaums cobbling together computer workstations from vintage cameras and manual typewriters. Local enthusiasts are mounting steampunk exhibits, writing books, creating objets d’art, and dressing up in steampunk garb for live-action role playing games.

To be sure, steampunk has been part of the cultural conversation for the past several years, as DIY-ers embraced the hand-wrought, Steam Age aesthetic over high-tech gloss. But recently, it seems to be gaining a wider appeal, especially here.

“Boston lends itself to steampunk,’’ said Kimberly Burk, who researched steampunk as a graduate student at Brandeis. “You have the MIT tinkerers, the co-ops in JP, the eco-minded folks.’’

Both a pop culture genre and an artistic movement, steampunk has its roots in 19th- and early-20th-century science fiction like Jules Verne’s “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’’ and H.G. Wells’s “The Time Machine.’’ Its fans reimagine the Industrial Revolution mashed-up with modern technologies, such as the computer, as Victorians might have made them. Dressing the part calls for corsets and lace-up boots for women, top hats and frock coats for men. Accessories include goggles, leather aviator caps, and the occasional ray gun. And there’s a hint of Sid Vicious and Mad Max in there, too.

Still, steampunk defies easy categorization. It can be something to watch, listen to, wear, build, or read, but it’s also a set of loose principles. Steampunk attracts not only those who dream of alternative history, but those who would revive the craft and manners of a material culture that was built to last.

“The acceleration of the present leaves many of us uncertain about the future and curious [about] a past that has informed our lives, but is little taught,’’ said Martha Swetzoff, an independent filmmaker on the faculty of the Rhode Island School of Design who is directing a documentary on the subject. “Steampunk converses between past and present.’’

It also represents a “push back’’ against throw-away technologies, Swetzoff said, and a “culture hijacked by corporate interests.’’

For Burk, steampunk is more akin to the open source software movement than a retro-futuristic world to escape into. “Steampunk isn’t about how shiny your goggles are,’’ she said. “It’s about how cleverly you create something.’’

The urge to rescue and repurpose forgotten things led the Rosenbaums to spread the steampunk gospel. They’ve founded two companies: Steampuffin and ModVic, which infuse and rework 19th-century objects and homes with modern technology. They’re working on a book about the history of steampunk design. And, hoping some steampunker might want to live in a pimped-out Victorian crib, they purchased a second home in North Attleboro, restored it using their “back home to the future’’ philosophy, and put it on the market.

Bruce is also curating two steampunk exhibits. One will be displayed at Patriot Place’s new “20,000 Leagues’’ attraction, an “hourlong, walk-though steampunk adventure,’’ scheduled to open in December, according to creator Matt DuPlessie.

Meanwhile, “Steampunk: Form and Function, an Exhibition of Innovation, Invention and Gadgetry’’ recently opened at the Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation in Waltham, a former textile mill already filled with steam engines and belt-driven machines.

“Form and Function’’ includes a juried show of steampunked objects (many by local artists) like a steam-electric hybrid motorcycle called “the Whirlygig,’’ an electric mixer powered by a miniature steam engine, and a flash drive made with brass, copper, and glass. Perhaps the most impressive piece is a rehabbed pinball machine whose guts look like Frankenstein’s lab — down to the colored fluids bubbling through vintage glass tubes.

“I like giving things a new life,’’ said Charlotte McFarland of Allston, exhibiting her first-ever steampunk creation, “Spinning Wheel Generator.’’

Such functional art objects tap into a nostalgia for a mechanical, not electronic, age. Unlike the wireless signals, microwaves, and motherboards of today, the 19th century’s gears, pistons, and tubes were visible and visceral. While the workings of a laptop can seem impenetrable, we can fathom the reality of moving parts.

“As the world becomes more digital, the world less and less appreciates machines, which will be lost,’’ said Elln Hagney, the museum’s acting director. “We are trying to train a new generation to appreciate this and keep these machines running.’’

Some of the most committed local steampunkers dress up in period garb and take part in live-action role playing games. Most “LARPs’’ (think Dungeons & Dragons but in costume) are swords and sorcery-based, but Boston’s Steam & Cinders is one of only a couple of steampunk-themed LARPs anywhere.

Once a month, some 100 players gather for a weekend at a 4-H camp in Ashby. The game’s premise? A crashed dirigible has stranded folks at a frontier town called Iron City, next to a mysterious mine. Engineers, grenadiers, and aristocrats vie for supremacy. There are plenty of robots to fight (players dressed in cardboard costumes sprayed with metallic paint), and potions to mix (appealing to the mad scientist in us all). Players stay in character for 36 hours straight.

“Yes, it’s a fantasy world and it’s not England,’’ said Steam & Cinders founder Andrea DiPaolo of Saugus. “But getting to dress in British garb and speak in a British accent is something I enjoy.’’

Meanwhile, publishers are striking while the steampunk iron is hot.

“We can tap into the enthusiasm of a reader who can imagine an alternative version of the 19th century,’’ said Cambridge resident Ben H. Winters, author of this summer’s mash-up book “Android Karenina.’’

Winters steampunked Tolstoy’s novel by re-envisioning Anna Karenina in a 19th-century Russia with robotic butlers, mechanical wolves, and moon-bound rocket ships. Sample line: “When Anna emerged, her stylish feathered hat bent to fit inside the dome of the helmet, her pale and lovely hand holding the handle of her dainty ladies’-size oxygen tank . . .’’

“Hopefully,’’ explained Winters, who also wrote 2009’s “Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters,’’ “we’ll be adding to the fandom of the mash-up novel by introducing a new fan base: the sci-fi crowd.’’

Climb to Bruce Rosenbaum’s third-floor study and you feel as if you’ve entered one of those mash-ups. The attic space feels like a submersible, packed with portholes, nautical compasses, and a bank vault door. His desk is ornate and phantasmagorical, ringed with pipes from a pipe organ. It’s a place where you can imagine Captain Nemo banging out an ominous dirge.

“There’s freedom with steampunk,’’ Melanie added. “Almost anything goes.’’

+++++++

A Steampunk Primer

Not sure who or what put the punk into steam? Here’s a quick-and-dirty intro to some of the culture’s roots and most influential works, plus ways to connect to the steampunk community.

Books

Jules Verne: “From the Earth to the Moon” (1865), “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea” (1869)

H.G. Wells: “The Time Machine” (1895), “The War of the Worlds” (1898), “The First Men in the Moon” (1901)

K.W. Jeter : “Morlock Night” (1979)

William Gibson and Bruce Sterling: “The Difference Engine” (1990)

Paul Di Filippo: “Steampunk Trilogy” (1995)

Philip Pullman: “His Dark Materials” trilogy (1995-2000)

Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill: “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” (comic book series, 1999)

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, editors: “Steampunk” (2008)

Dexter Palmer : The Dream of Perpetual Motion (2010)

Movies and TV

“20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” (1954)

“The Wild Wild West” (TV series: 1965–1969); “Wild Wild West” (movie: 1999)

“The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” (2003)

“Steamboy” (anime film: 2004)

“Sherlock Holmes” (2009)

“Warehouse 13” (TV series: 2009-)

Steampunk info/community on the web:

The Steampunk Empire: The Crossroads of the Aether, thesteampunkempire.com

Steampunk magazine, steampunkmagazine.com

“Steampunk fortnight” blog, tor.com/blogs/2010/10/steampunk-fortnight-on-torcom

The Steampunk Workshop, steampunkworkshop.com

Other resources:

computer/console games: Myst (1993); BioShock (2007)

Templecon convention (Feb 4-6, 2011; Warwick, RI), templecon.org

Steam & Cinders live-action role-playing game (Boston), be-epic.com

Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation (Waltham, MA), crmi.org (“Steampunk: Form and Function” exhibit through May 10; Steampunkers “meet up” Dec. 19; steampunk course March, 2011; New England Steampunk Festival April 30-May 1, 2011)

Steampuffin appliances and inventions and ModVic Victorian and steampunk home design (Sharon, MA), steampuffin.com, modvic.com

--- Ethan Gilsdorf

When literary authors slum in genre

There’s a curious phenomenon happening out there in LiteraryLand: The territory of genre fiction is being invaded by the literary camp.

There’s a curious phenomenon happening out there in LiteraryLand: The territory of genre fiction is being invaded by the literary camp.

While it could be argued that literary writers have always borrowed from fantasy, science fiction and horror, even stolen genre's best ideas, I think there's a new and significant shift happening in the past few years.

Take Justin Cronin, writer of respectable stories, who recently leaped the chasm to the dystopian, undead-ridden realm of Twilight. With The Passage, his post-apocalyptic, doorstopper of a saga, the author enters a new universe, seemingly snubbing his former life writing “serious books” like Mary and O’Neil and The Summer Guest, which won prizes like Pen/Hemingway Award, the Whiting Writer’s Award and the Stephen Crane Prize. Both books of fiction situate themselves solidly in the camp of literary fiction. They’re set on the planet Earth we know and love. Not so with The Passage, in which mutant vampire-like creatures ravage a post-apocalyptic U.S. of A. Think Cormac McCarthy’s The Road crossed with the movie The Road Warrior, with the psychological tonnage of John Fowles’ The Magus and the “huh?” ofThe Matrix.

Now comes Ricky Moody, whose ironic novels like The Ice Storm andPurple America were solidly in the literary camp, telling us about life in a more-or-less recognizable world. His latest novel, The Four Fingers of Death, is a big departure, blending a B-movie classic with a dark future world. The plot: A doomed U.S. space mission to Mars and a subsequent accidental release of deadly bacteria picked up on the Red Planet results in that astronaut’s severed arm surviving re-entry to earth, and reanimating to embark on a wanton rampage of strangulation.

And there’s probably other examples I’m forgetting at the moment.

So what’s all this forsaking of one’s literary pedigree about?

It began with the flipside of this equation. It used to be that genre writers had to claw their way up the ivory tower in order to be recognized by the literary tastemakers. Clearly, that’s shifted, as more and more fantasy, science fiction, and horror writers have been accepted by the mainstream and given their overdue lit cred. It’s been a hard row to hoe. J.R.R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Philip Pullman and others helped blaze the trail to acceptance. Now these authors have been largely accepted into the canon. You can take university courses on fantasy literature and write dissertations on the homoerotic subtext simmering between Frodo and Sam. A whole generation, now of age and in college, grew up reading (or having read to them) the entire oeuvre of Harry Potter. That’s a sea change in the way fantasy will be seen in the future—not as some freaky subculture, but as widespread mass culture.

Yes, Margaret Atwood and Doris Lessing have delved into genre, although their works (A Handmaid's Tale, for example) was always taken as highbrow. Perhaps a better example: Stephen King, considered a hack horror writer for years who began publishing in the New Yorker in 1990. One wonders why the New Yorker finally caved and let him in the doors --- is this an implicit acknowledgement of his popularity? Or had King's writing gotten better. In any case, it's was a shocker when he began racking up impressive literary kudos, like in 2003 when the National Book Awards handed over its annual medal for distinguished contribution to American letters to King. Recently in May, the Los Angeles Public Library gave its Literary Award for his monstrous contribution to literature.

Now, as muggles and Mordor have entered the popular lexicon, the glitterati of literary fiction find themselves “slumming” in the darker, fouler waters of genre. (One reason: It’s probably more fun to write.) But in the end, I think it’s all about call and response. Readers want richer, more complex and more imaginative and immersive stories. Writers want an audience, and that audience increasingly reads genre. Each side—literary and genre—leeches off the other. The two camps have more or less met in the middle.

One wonders who’s going to delve into the dark waters next—Philip Roth? Salman Rushdie? Toni Morrison? Actually, it turns they already (sort of) have --- Roth explores alternative history in The Plot Against America;

Rushdie's "Magical Realism," of Midnight's Children, in which children have superpowers. You might even argue that Morrison's Beloved is a ghost story.

[thanks to readers at Tor.com, where this post originally appeared, for catching some errors and helping me revise this into a better essay]

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, which comes out in paperback in September. Contact him through his website,www.ethangilsdorf.com