Follow my insane itinerary?

Hey Boston travel fans: I dare you to do all this in Boston in a mere 36 Hours. Here's my insane itinerary for the New York Times Travel section "36 Hours in ..." series.

All I needed to know about life I learned from “Dungeons & Dragons”

I was lucky enough to publish this piece on Salon.com, using the occasion of D&D's 40th anniversary this month to wax poetical about all the life lessons the game taught me.

I was lucky enough to publish this piece on Salon.com, using the occasion of D&D's 40th anniversary this month to wax poetical about all the life lessons the game taught me. I was lucky enough to publish this piece on Salon.com, using the occasion of D&D's 40th anniversary this month to wax poetical about all the life lessons the game taught me.

I was lucky enough to publish this piece on Salon.com, using the occasion of D&D's 40th anniversary this month to wax poetical about all the life lessons the game taught me.

Here's an excerpt:

I played a lot of D&D back in the 1970s and 1980s. After conquering me, D&D went on to transform geek culture. Not only had D&D invented a new genre of entertainment — the role-playing game — but it practically gave birth to interactive fiction and set the foundation for the modern video game industry. Into “Halo” or “Call of Duty”? You’re playing an incredibly sophisticated version of a D&D dungeon crawl.

After a long hiatus, I play the game again now, as a 47-year-old, mostly grown-up person. Today, with my +5 Goggles of Hindsight, I can see how D&D was subtly helping me come of age. Yes, it’s a fantasy game, and the whole enterprise is remarkably analog, powered by face-to-face banter, storytelling and copious Twizzlers and Doritos. But like any pursuit taken with seriousness (and the right dose of humor), Dungeons & Dragons is more than a mere game. Lessons can be applied to the human experience. In fact, all I really need to know about life I learned by playing D&D.

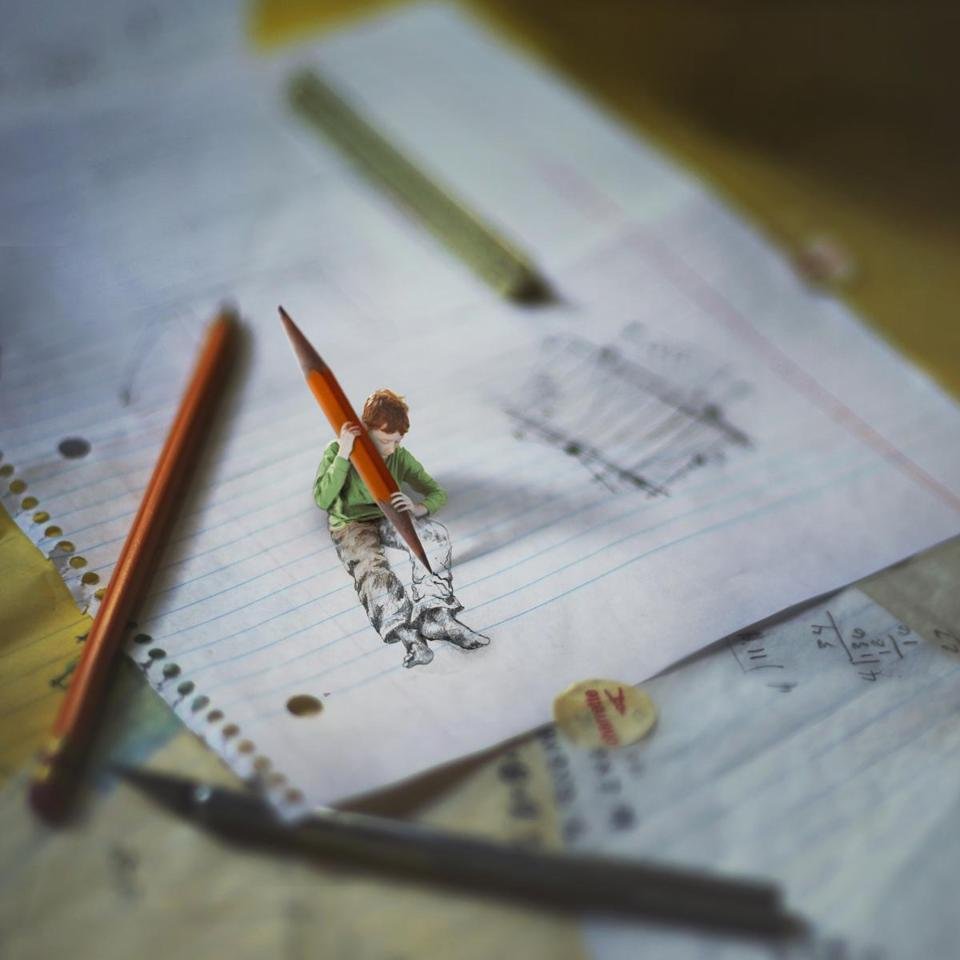

A kid who brings miniature worlds to life

NATICK — Sometimes, the world can seem overwhelming. Overbearing. If only you were tiny enough to build a house out of cards and climb inside, or escape to a miniature treehouse suspended between stalks of broccoli.

NATICK — Sometimes, the world can seem overwhelming. Overbearing. If only you were tiny enough to build a house out of cards and climb inside, or escape to a miniature treehouse suspended between stalks of broccoli.

Or better yet, just fly away. Fold a giant paper airplane, then grasp its thin fuselage for dear life and sail across a field into summertime.

Such is Zev Hoover’s fanciful photographic take on reality. His arresting images evoke a wonderland of imaginary environments, built from f-stops and pixels, and hinting at characters with secret stories to tell.

Hoover’s work, which he posts on the photo sharing site Flickr using the handle “Fiddle Oak” (a play on “Little Folk”), has caught fire across the Internet. He has been profiled in the media and on design and photography blogs. On Monday, he will fly to New York to appear on ABC’s “Good Morning America Live” webcast.

One post touting his “surreal photo manipulations” has received 108,000 Facebook likes.

“Maybe a million people saw it,” said the slightly stunned Hoover, who is only 14.

-5.jpg)

COLM O’MOLLOY FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

“He’s enjoying this little ride,” said his father, Jeff. “But he’s familiar with Andy Warhol’s idea of 15 minutes of fame and realizes this may be transitory.”

The skinny teen deadpanned, “If I was older, it wouldn’t make as good of a story.”

But it’s Hoover’s talent that has captured imaginations. A film production company contacted him about designing a movie poster. He has been approached by a publisher for a potential narrative photo textbook project. Nikon World magazine asked him to contribute a photo. A lens manufacturer sent him a free lens, saying only: “Take some pictures with it.”

No doubt he will. Plenty of his peers would be happy playing soccer or video games, but not Hoover. He needs to be creating. “I get anxious if I’m not doing something,” he said, sitting outside his family’s Natick home this week. “What’s next?”

His series of “Little Folk/Fiddle Oak” images began during a walk in the woods with sister, Aliza. He remembers thinking, “Oh, wouldn’t little people be cool?” Crouching near the ground, he imagined seeing the world from their perspective. He felt the miniature genre had never been done in photography — “at least not very well.”

“There’s a fine line to walk between having it be too abstract and having it be too cheesy-obvious,” he said.

He performs his sleight of hand in Photoshop, which he taught himself via Internet tutorials.

Read the rest of the front page Boston Globe story. For a photo gallery of Zev's work, look here.

Writing Our Way Through The Terror

A woman carries a girl from their home as a SWAT team searching for a suspect in the Boston Marathon bombings enters the building in Watertown, Mass., Friday, April 19, 2013. (Charles Krupa/AP)An author friend writes a tribute to his country on his Facebook page. A stay-at-home mom, guarding her bevy of children, becomes a citizen reporter on the scene in Watertown, tweeting about the view from her backyard of snipers staking out a position on the roof of her garden shed. An otherwise non-aspiring writer is inspired to try his hand at capturing his version of this past week’s dreamy miasma of exhausting, hand-wringing events.

A woman carries a girl from their home as a SWAT team searching for a suspect in the Boston Marathon bombings enters the building in Watertown, Mass., Friday, April 19, 2013. (Charles Krupa/AP)An author friend writes a tribute to his country on his Facebook page. A stay-at-home mom, guarding her bevy of children, becomes a citizen reporter on the scene in Watertown, tweeting about the view from her backyard of snipers staking out a position on the roof of her garden shed. An otherwise non-aspiring writer is inspired to try his hand at capturing his version of this past week’s dreamy miasma of exhausting, hand-wringing events.

As we Boston-area residents have been recovering from the Boston Marathon bombings, the lockdown, and from our media hangovers, out gushed the words, like a fresh wound. Not spoken words, which can evaporate as soon as they are voiced. But stories, written down.

Sure, we’ve all experienced the flurry of hastily dashed-off texts, sent to loved ones to check in, to say, “We are safe.” But even before the dust settled on Boylston Street, I’d noticed a burst of blog posts, Facebook posts, and other personal accounts popping up on the Internet. Those longer stories that cannot be contained in a mere tweet.

All these written words prove our need to find our place within the events. To be part of the story, to insert our own heart and mind into this larger narrative. Who doesn’t want to comment, to communicate, to reflect, to engage in some way? Or, as Neil Diamond himself belted out at Fenway Park, to use words as, “Hands, touching hands / Reaching out, touching me, touching you”?

This urge to participate and to tell one’s individual story humanizes pain and makes big, sweeping events human-scaled. The tradition is as old as Homer and the Icelandic Sagas. We cope with trauma by injecting ourselves into the wider story. The gesture says, “I, too, was there.” The gesture also says, “This is how I process grief.” Story helps transform chaos, crisis, and helplessness into something we can retell, and therefore transcend.

Read the rest of my commentary "Writing Our Way Through The Terror" for NPR affiliate WBUR

How do you have a day without creativity, imagination, and thought?

WHO

|

Taking the time to stop |

| Drake Patten | |

|

WHAT |

|

|

Drake Patten knows what looms if arts and culture disappear. A lifelong arts advocate and former director of the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities, Patten is now the executive director of The Steel Yard, a Providence-based center that uses the industrial arts to foster community revitalization and workforce development. She recently co-founded Culture Stops!, a volunteer-run nationwide day of action (or rather, inaction) on Thursday, March 10, to draw attention to the impact of proposed federal budget cuts on the creative sector. Q. Your website www.culturestops.org asks people “to witness a world devoid of creativity, imagination and thought: America after culture stops.’’ How do you have a day without creativity, imagination, and thought? A. This is a day about absence. This Culture Stops! movement is about what is there when it’s not there. We want people to stop and mark the day. Q. How would it work? A. People who are performing, for example music, could stop their performance and try to educate the audience, or leave the stage and join the audience and look at the blank stage. We have talked to people who have said they would cover their works of art with a black cloth. Or simply put up the Culture Stops! logo on their website or Facebook page. Q. So you don’t necessarily want to shut down culture for the day. A. In the Culture Stops! call to action, we say “stop work for eight minutes to a full eight hours.’’ You choose. Keep your store open that sells local art but put something in the bag that says, “You just bought something on Culture Stops! day.’’ To say you should just stop working that day and alienate your clients, that’s not realistic. But the education of clients is necessary. Q. How widespread is participation so far? A. We just launched [last week]. We are hearing from every state but I think five. What is great is that people are saying that they are prepared to take on what is immediately local. Q. How did this idea originate? A. Culture Stops! began around a kitchen table in Cranston, R.I., with five people, one dog, and $87. I was speaking to my colleagues about our fears. It’s the fear about not being able to do our work, and living in a nation where arts and culture is not valued. In a human way this translates to darkness. It’s like a black stage. Q. How do you answer those who claim that, in a down economy, arts and culture are luxuries, that we all have to tighten our belts? A. When you set a budget, you are setting the program. You are saying publicly that arts and culture have value or they don’t. We have increasingly seen over the years the cultural budget line being embattled. While we’re very clear this budget will demand sacrifice across the board, we feel this is disproportionate. Q. It seems that what you call “the creative sector’’ could do a better job explaining itself. A. The cultural sector is a critical part of the national economy with big impact nationwide. The non-profit arts sector represents the equivalent of 5.7 million full-time jobs, including many in a range of related industries traditionally not thought of as part of the arts world. That’s $166.2 billion annually in economic activity and more than $12.5 billion in federal income taxes. This isn’t a niche market developed around earmarks. These are mainstream American jobs. It’s not that it’s just artists. It’s the skills that go into every sector. IBM recently put out a report that asked what does the business world really value in leadership? Creativity, innovation, imagination. Q. Let’s say you’ve paid $20 to go to a concert or play on March 10. Are you worried some people might get upset if that experience is interrupted? A. I’m sure it could make some people angry. But I do think it’s very important to be exposed to the idea that art goes away. We in this culture, we have a lot. But we don’t have the experience of taking away. If people are upset about it, that might be the best thing. I was inspired by what came out of Egypt. America knew at one point how to take to the streets. Perhaps we are at that point again.

Interview was condensed and edited. Ethan Gilsdorf can be reached at www.ethangilsdorf.com. |