Is steampunk the new goth?

Is steampunk the new goth?

By Ethan Gilsdorf, December 29, 2010

(links to images on the Christian Science Monitor site)

A Steampunk mantel clock by Roger Wood of Ontario is valued at $1,500. It’s part of an exhibition titled (with Steampunkish ornament), ‘Steampunk, Form and Function, an Exhibition of Innovation, Invention and Gadgetry’ at a Waltham, Mass., museum. [photo: Melanie Stetson Freeman/Christian Science Monitor Staff]Some pop culture genres such as Tolkienesque fantasy imagine a magical past of strange races and global quests. Others, such as hard-core dystopian science fiction, warn against a future marred by apocalyptic meltdown.

A Steampunk mantel clock by Roger Wood of Ontario is valued at $1,500. It’s part of an exhibition titled (with Steampunkish ornament), ‘Steampunk, Form and Function, an Exhibition of Innovation, Invention and Gadgetry’ at a Waltham, Mass., museum. [photo: Melanie Stetson Freeman/Christian Science Monitor Staff]Some pop culture genres such as Tolkienesque fantasy imagine a magical past of strange races and global quests. Others, such as hard-core dystopian science fiction, warn against a future marred by apocalyptic meltdown.

Then comes steampunk, a hybrid vision of a past that might appear in the future – or a future that resides, paradoxically, in the spirit of another age.

No, you're not stuck in some goofy concept album by The Moody Blues. Steampunk is a fantasy made physical, made of brass and wood and powered by steam, born of the Industrial Age and inspired by the works of H.G. Wells and Jules Verne. It takes form both as an aesthetic movement and a community of artists; role-players; visionaries; and those who use the tools of literature, film, music, fashion, science, design, architecture, and gaming to manifest their visions.

"[Steampunk is] drawing on actual history. You can pull into it what you're into and put your spin on it. It's accessible yet expandable," says Jake von Slatt (real name: Sean Slattery, of Littleton, Mass.), who likens the philosophy behind steampunk to the open-source software movement. "There is a real focus on sharing, exploring things together, building community."

Steampunkers gather in conventions to exchange ideas – plus, they know how to dress to the nines and party like it's 1899.

Mr. von Slatt, who came of age in the era of punk rock, new wave, and Goth, has always been a tinkerer. Steampunk lets him "revisit youthful enthusiasms," he says. Now he creates intricately crafted anachronistic objects: for example, computer keyboards taken apart and rebuilt with brass, felt, and keys from antique manual typewriters. He's transformed a 1989 school bus into a wood-paneled "Victorian RV," which he uses to travel to steampunk conventions.

Currently, he's "steampunking" a fiberglass, 1954-style Mercedes kit car, tricking it out with salvaged gauges and lights from other cars and gold filigree trim. Drawn to steampunk's "do-it-yourself, making something from nothing" mantra, von Slatt scavenges most of his components from the dump.

Roots in a 1960s TV series

Steampunk was first introduced as a literary subgenre. William Gibson and Bruce Sterling's 1990 novel "The Difference Engine" popularized the idea of an alternate history where the Industrial Revolution-level technology of pistons and turbines, not electricity, powers modern gadgets, as Victorians might have designed them. But even way back in 1960s, the television series "The Wild Wild West" helped define the genre. The sci-fi western featured a train outfitted with a laboratory and featured protagonists who were gadgeteers.

Today, steampunk's reach has exploded, from Boston to San Francisco's Bay Area, to Britain, New Zealand, Japan, and beyond.

"Steampunk is definitely growing in popularity," says Diana Vick, vice chair of Steamcon, an annual convention in Seattle that doubled its attendance when it held its second meeting in November. "I believe it is due in part to the fact that it is a rejection of the slick, soulless, mass-produced technology of today and a return to a time when it was ornate and understandable."

This year, Steamcon celebrated what its website called the Weird Weird West. It notes: "Imagine the age of steam on the wild frontier ... roughriders on mechanical horses, mad inventors ... mighty steam locomotives ... airships instead of stagecoaches."

Every culture that embraces steampunk seems to make it their own. Patrick Barry, a member of New Zealand's League of Victoria Imagineers, has seen myriad international examples. "All have a different flavour, world vision and cultural base for the artists and writers to draw from and it shows," he writes via e-mail. Even in his tiny hometown of Oamaru, steampunk has taken off. Three groups have recently mounted an exhibition, a fashion show, and run several events. "Oamaru has a population of about 13,000 people. We had 11,000 people visit the exhibition over its six week [run]."

Previously, most works in the genre would have been set only in the Industrial Age. Over time, explains Dexter Palmer, author of the novel "The Dream of Perpetual Motion," the term "steampunk" has undergone "definition creep." "Nowadays the label's much more comprehensive, and seems to refer to any retrofuturistic or counterfactual work that features machines with lots of gears, or lighter-than-air flying craft, or similar sorts of things."

Some works have been retroactively embraced as part of the genre. For example, Terry Gilliam's dystopian satire, "Brazil," is now considered steampunk even though the film was not called steampunk when it was released in 1985.

In Mr. Palmer's novel, a greeting-card writer who is imprisoned aboard a zeppelin must confront a genius inventor and a perpetual motion machine. The author created a set of rules for his fictional universe: While things might be "scientifically implausible" to the reader, they would be "self-consistent and plausible to the inhabitants of the imaginary world." He based his ideas on source materials that predicted life in the year 2000 and then designed gadgets that seemed modern, but used turn-of-the-century tech. For example, there's an answering machine in the novel that functions by recording to a wax cylinder.

'It wants to teach us things'

"One of the really wonderful things about Steampunk is that it, more than any other subculture, seems to want to teach us things," von Slatt wrote on his blog at steampunkworkshop.com. And, like the punk and Goth movements before it, steampunk teaches another way of looking at the world.

Ms. Vick adds that another appeal lies in its largely optimistic and romantic, not dark and cautionary, outlook. "We also embrace and foster good manners and dressing up, which are both sorely lacking in society today," she says.

Indeed, dedicated steampunkers are lured by fashion. To dress up as a privateer and pilot flying machines powered by "lift-wood," or play a mad scientist who meddles in alchemy, the required accouterments include corsets, top hats, and lace-up boots; military medals, parasols, and aviator goggles.

Bruce and Melanie Rosenbaum aren't particularly into costuming, but when attending an event they will break out period garb. Their businesses, ModVic and SteamPuffin, offer home remodeling and design services for steampunking Victorian-era homes, an idea they applied to their own 1901 house in Sharon, Mass. They loved the turn-of-the-century fantasy but, Bruce says, "you don't want to live in the 19th century in terms of conveniences." So they retrofitted modern appliances or hid them behind facades of functional art. Combining old and new, their living room sports a plasma TV framed by an antique wooden mantel.

Upstairs, Bruce's attic office incorporates portholes, a bank vault door, and computer workstation made from an antique desk and pipes from a pump organ. You can almost see the ghost of Jules Verne hammering out a few e-mails.

"How much more fun is it to make something ornate and beautiful, rather than boring and unadorned?" asks Melanie. The couple is working on a book project, and recently curated two exhibits in the Boston area.

Tom Sepe, an artist exhibiting in one of them, the "Steampunk Form & Function" show at the Charles River Museum of Industry & Innovation in Waltham, Mass., shipped his "Whirlygig," a "steam-electric-hybrid motorcycle," from his workshop in Berkeley, Calif. The circus performer discovered steampunk via the Burning Man art community, and looks at his life as art. "Every choice we make is part of a performance," he says. "Every object we make or touch becomes an artifact of who we are and how we have been."

For Mr. Sepe, "three crucial elements" keep him engaged in the steampunkmaker culture: the "warmth factor" of its handmade materials, its functionality, and whimsy – "free thinking imagination and fun." Unlike other art forms, he says, "It doesn't take itself too seriously."

And whereas other genre fans can niggle over the small stuff, steampunk tends to be more open-ended. Jeff Mach, one of the partners behind New Jersey's Steampunk World's Fair, remembers Goths back in the 1990s sniping at one another for not being "Goth enough." No so with this latest, more inclusive cultural mashup. "It's not starting from a single point but many points," he says.

Many suggest steampunk is the next Goth, or even bigger. "I think this is the beginning of steampunk as a new sort of thing, as a pop culture phenomenon," says von Slatt. "I think it's the tip of the iceberg."

16 books to buy the geek on your list

16 books to buy the geek on your list

Trouble finding the perfect last-minute gift for that geek on your shopping list? Here are 16 great books covering all stripes of geekery

Just in time .... a Geek Book Gift Guide

'Twas the night before Christmas, when through the black hole

Not a fanboy or girl was stirring, not even a troll;

The MacBooks were placed near the Wi-fi with care,

In hopes that St. Geekolas soon would be there.

Have you been a good little geek this year? Have you kept your PS3 and Xbox consoles all shiny and neat? Did you get all A’s in Elvish and Klingon and Shyriiwook (aka Wookiee Speak)? Did you roll all 20’s the last time you went dungeon crawling? If so, perhaps you’ll find one of these geek-eriffic books under the tree this year.

But if you haven’t been good ... Well, Sauron’s eye, I mean Santa’s eye, is ever watchful. So you better watch out.

My Best Friend Is a Wookiee: A Memoir, One Boy’s Journey to Find His Place in the Galaxy

by Tony Pacitti ($19.95, Adams Media)

Certified Star Wars geek (and Massachusetts native) Tony Pacitti charts his life in relation to the Trilogy—from pathetic childhood and adolescence to Luke Skywalker-like coming of age. We see a painfully shy kid slowly trying out the Jedi-like powers of adulthood and using the transformative Force (and forces) of the Star Wars universe to get him there. A hyperdrive tour through Star Wars fandom that's more fun than shooting womp rats in Beggar's Canyon. But “My Best Friend Is a Wookiee” also a comical, tender, no-punches-pulled coming of age memoir.

by Leo Tolstoy and Ben H. Winters ($12.95, Quirk Books)

What happens when you mash-up “Anna Karenina” with the world of 19th century Russia, this time retro-fitted with robotic butlers, mechanical wolves and moon-bound rocketships? You get “Android Karenina,” from the same folks who brought us “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies” and “Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters.” Here’s a sample line from Winters’ steampunked Tolstoy: “When Anna emerged [from the rocket], her stylish feathered hat bent to fit inside the dome of the helmet, her pale and lovely hand holding the handle of her dainty ladies’-size oxygen tank ...” A fun tongue-in-cheek romp for literature majors and science fiction aficionados alike.

We, Robot: Skywalker's Hand, Blade Runners, Iron Man, Slutbots, and How Fiction Became Fact

by Mark Stephen Meadows ($19.95, Lyons Press)

If you grew up like I did on a steady diet of “The Jetsons,” “The Six Million Dollar Man,” “Star Wars,” and “The Terminator,” then you’ve been wondering when all your robot fantasies might become true. But unlike personal jet packs (never happened) and hover craft (another back-of-comic-book pipe dream), cyborgs, androids, and avatars are real. With wit and insight, Mark Stephen Meadows separates science fiction from actual fact, navigating the ethically sketchy territory of domestic robots and autonomous military robots, artificial hands and artificial emotions. “We, Robot” raises the crucial questions that robot-makers largely ignore. In doing so, Meadows shows us that in our quest to create more and more life-like robots, we’ve become more robotic ourselves.

The Lord of the Rings Location Guidebook: Extended Edition

by Ian Brodie ($24.95, HarperCollins)

When I traveled to New Zealand to research my book “Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks,” and embarked on my own Lord of the Rings filming location geek-out quest, this guidebook was indispensable. With its detailed maps, directions, insider information and exclusive movie stills—even GPS coordinates—I was able to find dozens of sites, from the Shire (Matamata) to Mordor (Mt Ruapehu in Tongariro National Park) to Arrowntown’s The Ford of Bruinen, location for the famed “If you want him, come and claim him!” scene. Perfect for the Tolkien freak planning his or her own LOTR adventure Down Under.

Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter

by Tom Bissell ($22.95, Pantheon)

Must video games remain mere entertainment?Could they provide narratives that books, movies, and other vehicles for story delivery can’t? Might they even aspire to art? Tom Bissell's new book "Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter" aims a tentative mortar shot at these targets. His investigation is bedrocked upon personal experience; along the way, we also meet game developers at such megaliths as Epic Games, Bio Ware, and Ubisoft. Thankfully, the book isn’t pure fanboy boosterism. Video games can be great, he says, but they can be “big, dumb, loud.’’ A master prose stylist, the erudite Bissell is frequently insightful in the analysis of his video game obsessions.

![]()

Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games With God

by Craig Detweiler, editor ($19.95, Westminster John Knox Press)

A thoughtful collection of essays at the cross-section of religious and media studies. The various contributors take on quirky topics such as the theological implications of apocalyptic video games like Halo 3, Grand Theft Auto IV, and Resident Evil; how avatars are changing social networks and our spiritual lives; and the medical ethics and theology in controversial games such as BioShock. Bonus material includes an interview with Rand Miller, cocreator of Myst and Riven, and other video game industry folks.

by Dexter Palmer ($24.99, St. Martin’s Press)

In the steampunk tradition comes this debut novel a greeting card writer imprisoned aboard a zeppelin who must confront a genius inventor and a perpetual motion machine. In creating his world, Palmer borrowed from archival source materials that predicted life how life would be in the year 2000, then retro-designed modern gadgets that use turn-of-the-19th-century technology. A kind of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” as Jules Verne might have envisioned it and a great, richly-imagined read.

Confessions of a Part-Time Sorceress: A Girl's Guide to the Dungeons & Dragons Game

by Shelly Mazzanoble ($12.95, Wizards of the Coast)

Dungeons & Dragons insider Mazzanoble (she now works for Wizards of the Coast, the company behind D&D) gives a sassy and informative look at D&D from the female gamer's POV. She tackles myths and realities of gamer stereotypes and proves that women should be, and increasingly are, welcome to roll dice and at Cheetos with the rest of the trolls. As Mazzanoble writes: “Let’s get one thing straight: I am a girly girl. I get pedicures, facials, and microderm abrasions. I own more flavors of body lotions, scrubs, and rubs than Baskin Robbins could dream of putting in a cone. ... I am also an ass-kicking, spell-chucking, staff-wielding 134 year-old elf sorceress named Astrid Bellagio.”

Star Wars Jesus: A Spiritual Commentary on the Reality of the Force

by Caleb Grimes ($17.95, WinePress Publishing)

Is Obi-Wan Jesus? Why does Yoda speak like a character from the Old Testament? What inspires our devotion to this mythical universe of Jedis, Dark Sides and “feeling the Force”? Grimes gives us a different take on the LucasFilm empire, one that sees the Star Wars stories as potentially as powerful and useful as the ones we learned in Sunday school. In my case, I missed church entirely, but that didn’t stop me from quoting “There is no try. Do or do not” as a kind of spirtual/philosophical mantra.

Collect All 21! Memoirs of a Star Wars Geek: The First 30 Years

by John Booth ($14.95, Lulu.com)

Not long ago, enviro-spiritual interpretations of “The Lord of the Rings” were all the rage. Now, paeans to “Star Wars” are popular. Here’s one that’s a deliciously warped nostalgia trip through Star Wars fandom. From collecting Kenner action figures to getting Star Wars birthday cakes from puzzled parents to scribbling fan letters to Harrison Ford and Carrie Fisher, Booth shamelessly flaunts his lifelong lust for all things Star Wars. Like a tractor beam, this endearing account draws us in and makes us reminisce about our own geeky obsessions.

A Guide to Fantasy Literature: Thoughts on Stories of Wonder and Enchantment

by Philip Martin ($16.95, Crickhollow Books)

A diverse and thoughtful examination of the so-called “fantasy” genre: from Middle-earth to Narnia, high fantasy to dark fantasy, fairy-tale fiction to magic realism and adventure-fantasy tales. Peppered with meaty quotes by J.R.R. Tolkien, J.K. Rowling, C.S. Lewis and Stephen King, Martin’s book provides a concise primer for those wondering why it is we’re drawn to tales of magic quests and heroic derring-do.

The Mythological Dimensions of Doctor Who

by Anthony Burge, Jessica Burke and Kristine Larsen, editors ($15.00, Kitsune Books)

Dr. Who fans, rejoice! This collection of essays takes a look at the mythological undercurrent in this classic BBC television series considered by the Guinness World Records as the “longest-running science fiction television show in the world” and "most successful" science fiction series of all time.” (Take that, Lucas and Roddenberry). Topics connect Dr. Who to Arthurian legend, Batman and medieval Scandinavian Valkyries. An engaging discussion for the serious traveler of the Whoinverse.

Unplugged: My Journey into the Dark World of Video Game Addiction

by Ryan G. Van Cleave ($14.95, HCI)

Most of the time, playing video games is fine, fun and perfectly harmless. But every now and then, a player gets a little too immersed in a game’s imaginary word. In Cleave’s case, the game was World of Warcraft, and his playtime turned into an 80-hour-a-week, life-wrecking addiction. “Unplugged” tells a cautionary tale of hitting rock bottom, wising-up and climbing out of the dungeon.

How to Survive a Garden Gnome Attack: Defend Yourself When the Lawn Warriors Strike (And They Will)

by Chuck Sambuchino ($14.99. Ten Speed Press)

Silly. Ridiculous. And a hoot. In the spirit of those “how to survive a zombie apocalypse” manuals comes this tome to tell us how to defend against the latest enemy. The book claims it is “the only comprehensive survival guide that will help you prevent, prepare for, and ward off an imminent home invasion by the common garden gnome.” Great color photos bring the spoofy goofiness alive.

by Carl Warner ($22.50, Abrams Image)

For the food geek on your list. Sumptuous, jaw-dropping, eye-popping, mouth-watering fantastical landscapes made entirely from real fruit of this earth: vegetables, cheeses, breads, fish, meat, and grains (and fruit, too). The 25 photographs take you on a trip around the world... and the sweet treat is each photo is followed by making-of insights into the creative process. Don’t read on an empty stomach.

Geek Dad: Awesomely Geeky Projects and Activities for Dads and Kids to Share

by Ken Denmead ($17.00, Gotham)

The title pretty much says it all. You’re a geek. You have a kid who’s a geek (or you want to turn your kid into a geek). Read this crafty book for ideas to share your love of science, technology, gadgetry and MacGyver. Engineer and wired.com’s Geek Dad editor Ken Denmead offers projects so you and your child can, among other things: 1) launch a video camera with balloons; 2) make the "Best Slip n' Slide Ever”; and 3) build a working lamp with LEGO bricks and CDs. Soon, together, you can rule the galaxy as father and son. Mwahahah!

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now in paperback. Follow his adventures and get more info on this book at /

Geek poetry contest winners!

The results are in!

The results are in!

We sponsored a geek poetry contest with GeekMom.com and here are the winning poems.

Readers of Geek Mom were asked to submit a poem in any form of their choosing (haiku, rap, free verse, Klingon sonnet) on any geeky topic: Tolkien, Star Wars, Star Trek, gelatinous cubes, World of Warcraft war chants, hobbit drinking songs, odes to Harry Potter, ballads to honor Gary Gygax.

Sample winning haiku:

Samwise and Frodo:

You think they’re about to kiss,

But they never do.

--Natalie Jones

Poems that somehow managed to work in the name "Ethan Gilsdorf" (which, according to legend, is either Elvish or Elvis) were hard to resist. Winners got autographed copies of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms.

Hope you enjoy! The rest of the bards' fabulous winning works can be read here.

You can also read the other non-winning but nonetheless worthy entries here

You must see Marwencol

[For more information on Marwencol, seehttp://www.marwencol.com/ ]

[For more information on Marwencol, seehttp://www.marwencol.com/ ]

Like all accomplished war photographers, Mark Hogancamp puts himself at risk.

He shoots fugitive moments of violence, anguish, and bravery. But Hogancamp’s work differs from others’ in one key respect: The combat zones he enters don’t entirely exist in the real world. It’s the battlefield of his emotions that he’s trying to capture on film.

Marwencol is a remarkable documentary about this peculiar man and the fictitious, painstakingly-detailed, 1/6-scale town he built in his yard. Set in Belgium during World War II and populated with dozens of buildings, military vehicles, and more than 100 foot-high, poseable action figures, Hogancamp’s simulacrum is called Marwencol.

“Everything’s real,’’ Hogancamp gushes at one point in the film, demonstrating how a tiny pistol in one soldier’s hands has a working hammer and replaceable clip. “That all adds to my ferocity of getting into the story. I know what’s inside every satchel,’’ he says.

Those contents include a stamp-size deed proving that Captain “Hogie’’ Hogancamp, the real man’s 12-inch alter ego, owns the doll-house-size, make-believe bar in this make-believe realm.

The fine line separating real from imagined is the focus of this poignant and provocative documentary, winner of the Jury Award for best documentary at the SXSW Film Festival. [Marwencol opens at selected theaters in more than 40 cities nationwide, starting in November and continuing into December and January. More info on theater dates here:http://www.marwencol.com/theaters/]

Geek pride comes to Providence

PROVIDENCE, R.I. (WRNI) - For role players, gamers and sci-fi fans alike, the term geek doesn't have the same sting it used to. In fact, many are now embracing that very term. You can include authors Ethan Gilsdorf and Tony Pacitti on that list. They'll both be panelists tonight in Providence for R2-D20, and Evening of Sci-Fi Fandom and Fantasy Gaming Geekery. WRNI's Elisabeth Harrison spoke to the two authors about the event.

Violent Video Games Are Good for You

[upcoming events with Ethan Gilsdorf: NYC/Brooklyn 11/22 (panel "Of Wizards and Wookiees" with Tony Pacitti, author of My Best Friend is a Wookiee); Providence, RI: 12/2 (also with Pacitti); and Boston (Newtonville 11/21 and Burlington 12/11) More info ...]

Violent Video Games Are Good for You

Rock and roll music? Bad for you. Comic books? They promote deviant behavior. Rap music? Dangerous.

Rock and roll music? Bad for you. Comic books? They promote deviant behavior. Rap music? Dangerous.

Ditto for the Internet, heavy metal and role-playing games. All were feared when they first arrived. Each in its own way was supposed to corrupt the youth of America.

It’s hard to believe today, but way back in the late 19th century, even the widespread use of the telephone was deemed a social threat. The telephone would encourage unhealthy gossip, critics said. It would disrupt and distract us. In one of the more inventive fears, the telephone would burst our private bubbles of happiness by bringing bad news.

Suffice it to say, a cloud of mistrust tends to hang over any new and misunderstood cultural phenomena. We often demonize that which the younger generation embraces, especially if it’s gory or sexual, or seems to glorify violence.

The cycle has repeated again with video games. A five-year legal battle over whether violent video games are protected as “free speech” reached the Supreme Court earlier this month, when the justices heard arguments in Schwarzenegger v. Entertainment Merchants.

Back in 2005, the state of California passed a law that forbade the sale of violent video games to those younger than 18. In particular, the law objected to games “in which the range of options available to a player includes killing, maiming, dismembering or sexually assaulting an image of a human being” in a “patently offensive way” — as opposed to games that depict death or violence more abstractly.

But that law was deemed unconstitutional, and now arguments pro and con have made their way to the biggest, baddest court in the land.

In addition to the First Amendment free speech question, the justices are considering whether the state must prove “a direct causal link between violent video games and physical and psychological harm to minors” before it prohibits their sale to those under 18.

So now we get the amusing scene of Justice Samuel Alito wondering “what James Madison [would have] thought about video games,” and Chief Justice John Roberts describing the nitty-gritty of Postal 2, one of the more extreme first-person shooter games. Among other depravities, Postal 2 allows the player to “go postal” and kill and humiliate in-game characters in a variety of creative ways: by setting them on fire, by urinating on them once they’ve been immobilized by a stun gun, or by using their heads to play “fetch” with dogs. You get the idea.

This is undoubtedly a gross-out experience. The game is offensive to many. I’m not particularly inclined to play it. But it is, after all, only a game.

Like with comic books, like with rap music, 99.9 percent of kids — and adults, for that matter — understand what is real violence and what is a representation of violence. According to a report issued by the Minister of Public Works and Government Services in Canada, by the time kids reach elementary school they can recognize motivations and consequences of characters’ actions. Kids aren’t going around chucking pitchforks at babies just because we see this in a realistic game.

And a strong argument can be made that watching, playing and participating in activities that depict cruelty or bloodshed are therapeutic. We see the violence on the page or screen and this helps us understand death. We can face what it might mean to do evil deeds. But we don’t become evil ourselves. As Gerard Jones, author of “Killing Monsters: Why Children Need Fantasy, Super Heroes, and Make-Believe Violence,” writes, “Through immersion in imaginary combat and identification with a violent protagonist, children engage the rage they’ve stifled . . . and become more capable of utilizing it against life’s challenges.”

Sadly, this doesn’t prevent lazy journalists from often including in their news reports the detail that suspected killers played a game like Grand Theft Auto. Because the graphic violence of some games is objectionable to many, it’s easy to imagine a cause and effect. As it turns out, a U.S. Secret Service study found that only one in eight of Columbine/Virginia Tech-type school shooters showed any interest in violent video games. And a U.S. surgeon general’s report found that mental stability and the quality of home life — not media exposure — were the relevant factors in violent acts committed by kids.

Besides, so-called dangerous influences have always been with us. As Justice Antonin Scalia rightly noted during the debate, Grimm’s Fairy Tales are extremely graphic in their depiction of brutality. How many huntsmen cut out the hearts of boars or princes, which were then eaten by wicked queens? How many children were nearly burned alive? Disney whitewashed Grimm, but take a read of the original, nastier stories. They pulled no punches.

Because gamers take an active role in the carnage — they hold the gun, so to speak —some might argue that video games might be more affecting or disturbing than literature (or music or television). Yet, told around the fire, gruesome folk tales probably had the same imaginative impact on the minds of innocent 18th century German kiddies as today’s youth playing gore-fests like “Left 4 Dead.” Which is to say, stories were exciting, scary and got the adrenaline flowing.

Another reason to doubt the gaming industry’s power to corrupt: More than one generation, mine included, has now been raised on violent video games. But there’s no credible proof that a higher proportion of sociopaths or snipers roams the streets than at any previous time in modern history. In fact, according to Lawrence Kutner and Cheryl K. Olson, founders of the Center for Mental Health and Media (a division of the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Psychiatry), and members of the psychiatry faculty at Harvard Medical School, as video game usage has skyrocketed in the past two decades, the rate of juvenile crime has actually fallen.

Children have always been drawn to the disgusting. Even if the ban on violent games is eventually deemed lawful and enforced in California, the games will still find their way into the hot little hands of minors. So do online porn, and cigarettes and beer. But these vices haven’t toppled Western civilization.

Not yet, anyway — although a zombie invasion or hurtling meteor might. Luckily, if you’re a good enough gamer, you’ll probably save the day.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now in paperback.

win free copies of FF&GG!

Two cool ways to win a copy of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks

Write a poem for wired.com/GeekDad/GeekMom

How do you win this coveted book, you ask? Give us a verse or two. Be it a free verse, a limerick, a sonnet, ahaiku, or a villanelle, on the geeky subject of your choosing (think “An Ode to Harry Potter” or the “Ballad of Gary Gygax”). Just put your entries in the comments webform here and we’ll choose the best five entries by Friday 11/19/10!Good luck, and geek on!

Sign up at Fiction Writers Review Facebook Page

Each week The Fiction Writers Review gives away several free copies of a book. All you have to do to be eligible for the weekly drawing is be a fan of their Facebook page. No catch, no gimmicks. Just a way to help promote books we love. Go here.

Picking up steam: Why is Boston the hub of steampunk?

Picking up steam

Mashing modern days with the Victorian age excites role players, artists, and other fans of steampunk

When Bruce and Melanie Rosenbaum bought a 1901 home in Sharon, they wanted to restore it top to bottom. And rather than force a modern interior design, they remodeled it with a Victorian twist.

In the kitchen, an antique cash register holds dog treats. A cast iron stove is retrofitted with a Miele cooktop and electric ovens. In the family room, a wooden mantle frames a sleek flat-screen TV, and hidden behind an enameled fireplace insert, salvaged from a Kansas City train station, glow LED lights from the home-entertainment system.

Unknowingly, the Rosenbaums had “steampunked’’ their home, that is, added anachronistic (and sometimes nonfunctioning) machinery like old gears, gauges, and other accoutrements that evoke the design principles of Victorian England and the Industrial Revolution.

“When we started this three years ago, we didn’t even know what steampunk was,’’ said Bruce, 48. “An acquaintance came through the house and said ‘You guys are steampunkers.’ I thought, ‘Wow, there’s a whole group out there that enjoys blending the old and new.’’

It’s not just the Rosenbaums cobbling together computer workstations from vintage cameras and manual typewriters. Local enthusiasts are mounting steampunk exhibits, writing books, creating objets d’art, and dressing up in steampunk garb for live-action role playing games.

To be sure, steampunk has been part of the cultural conversation for the past several years, as DIY-ers embraced the hand-wrought, Steam Age aesthetic over high-tech gloss. But recently, it seems to be gaining a wider appeal, especially here.

“Boston lends itself to steampunk,’’ said Kimberly Burk, who researched steampunk as a graduate student at Brandeis. “You have the MIT tinkerers, the co-ops in JP, the eco-minded folks.’’

Both a pop culture genre and an artistic movement, steampunk has its roots in 19th- and early-20th-century science fiction like Jules Verne’s “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’’ and H.G. Wells’s “The Time Machine.’’ Its fans reimagine the Industrial Revolution mashed-up with modern technologies, such as the computer, as Victorians might have made them. Dressing the part calls for corsets and lace-up boots for women, top hats and frock coats for men. Accessories include goggles, leather aviator caps, and the occasional ray gun. And there’s a hint of Sid Vicious and Mad Max in there, too.

Still, steampunk defies easy categorization. It can be something to watch, listen to, wear, build, or read, but it’s also a set of loose principles. Steampunk attracts not only those who dream of alternative history, but those who would revive the craft and manners of a material culture that was built to last.

“The acceleration of the present leaves many of us uncertain about the future and curious [about] a past that has informed our lives, but is little taught,’’ said Martha Swetzoff, an independent filmmaker on the faculty of the Rhode Island School of Design who is directing a documentary on the subject. “Steampunk converses between past and present.’’

It also represents a “push back’’ against throw-away technologies, Swetzoff said, and a “culture hijacked by corporate interests.’’

For Burk, steampunk is more akin to the open source software movement than a retro-futuristic world to escape into. “Steampunk isn’t about how shiny your goggles are,’’ she said. “It’s about how cleverly you create something.’’

The urge to rescue and repurpose forgotten things led the Rosenbaums to spread the steampunk gospel. They’ve founded two companies: Steampuffin and ModVic, which infuse and rework 19th-century objects and homes with modern technology. They’re working on a book about the history of steampunk design. And, hoping some steampunker might want to live in a pimped-out Victorian crib, they purchased a second home in North Attleboro, restored it using their “back home to the future’’ philosophy, and put it on the market.

Bruce is also curating two steampunk exhibits. One will be displayed at Patriot Place’s new “20,000 Leagues’’ attraction, an “hourlong, walk-though steampunk adventure,’’ scheduled to open in December, according to creator Matt DuPlessie.

Meanwhile, “Steampunk: Form and Function, an Exhibition of Innovation, Invention and Gadgetry’’ recently opened at the Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation in Waltham, a former textile mill already filled with steam engines and belt-driven machines.

“Form and Function’’ includes a juried show of steampunked objects (many by local artists) like a steam-electric hybrid motorcycle called “the Whirlygig,’’ an electric mixer powered by a miniature steam engine, and a flash drive made with brass, copper, and glass. Perhaps the most impressive piece is a rehabbed pinball machine whose guts look like Frankenstein’s lab — down to the colored fluids bubbling through vintage glass tubes.

“I like giving things a new life,’’ said Charlotte McFarland of Allston, exhibiting her first-ever steampunk creation, “Spinning Wheel Generator.’’

Such functional art objects tap into a nostalgia for a mechanical, not electronic, age. Unlike the wireless signals, microwaves, and motherboards of today, the 19th century’s gears, pistons, and tubes were visible and visceral. While the workings of a laptop can seem impenetrable, we can fathom the reality of moving parts.

“As the world becomes more digital, the world less and less appreciates machines, which will be lost,’’ said Elln Hagney, the museum’s acting director. “We are trying to train a new generation to appreciate this and keep these machines running.’’

Some of the most committed local steampunkers dress up in period garb and take part in live-action role playing games. Most “LARPs’’ (think Dungeons & Dragons but in costume) are swords and sorcery-based, but Boston’s Steam & Cinders is one of only a couple of steampunk-themed LARPs anywhere.

Once a month, some 100 players gather for a weekend at a 4-H camp in Ashby. The game’s premise? A crashed dirigible has stranded folks at a frontier town called Iron City, next to a mysterious mine. Engineers, grenadiers, and aristocrats vie for supremacy. There are plenty of robots to fight (players dressed in cardboard costumes sprayed with metallic paint), and potions to mix (appealing to the mad scientist in us all). Players stay in character for 36 hours straight.

“Yes, it’s a fantasy world and it’s not England,’’ said Steam & Cinders founder Andrea DiPaolo of Saugus. “But getting to dress in British garb and speak in a British accent is something I enjoy.’’

Meanwhile, publishers are striking while the steampunk iron is hot.

“We can tap into the enthusiasm of a reader who can imagine an alternative version of the 19th century,’’ said Cambridge resident Ben H. Winters, author of this summer’s mash-up book “Android Karenina.’’

Winters steampunked Tolstoy’s novel by re-envisioning Anna Karenina in a 19th-century Russia with robotic butlers, mechanical wolves, and moon-bound rocket ships. Sample line: “When Anna emerged, her stylish feathered hat bent to fit inside the dome of the helmet, her pale and lovely hand holding the handle of her dainty ladies’-size oxygen tank . . .’’

“Hopefully,’’ explained Winters, who also wrote 2009’s “Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters,’’ “we’ll be adding to the fandom of the mash-up novel by introducing a new fan base: the sci-fi crowd.’’

Climb to Bruce Rosenbaum’s third-floor study and you feel as if you’ve entered one of those mash-ups. The attic space feels like a submersible, packed with portholes, nautical compasses, and a bank vault door. His desk is ornate and phantasmagorical, ringed with pipes from a pipe organ. It’s a place where you can imagine Captain Nemo banging out an ominous dirge.

“There’s freedom with steampunk,’’ Melanie added. “Almost anything goes.’’

+++++++

A Steampunk Primer

Not sure who or what put the punk into steam? Here’s a quick-and-dirty intro to some of the culture’s roots and most influential works, plus ways to connect to the steampunk community.

Books

Jules Verne: “From the Earth to the Moon” (1865), “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea” (1869)

H.G. Wells: “The Time Machine” (1895), “The War of the Worlds” (1898), “The First Men in the Moon” (1901)

K.W. Jeter : “Morlock Night” (1979)

William Gibson and Bruce Sterling: “The Difference Engine” (1990)

Paul Di Filippo: “Steampunk Trilogy” (1995)

Philip Pullman: “His Dark Materials” trilogy (1995-2000)

Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill: “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” (comic book series, 1999)

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, editors: “Steampunk” (2008)

Dexter Palmer : The Dream of Perpetual Motion (2010)

Movies and TV

“20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” (1954)

“The Wild Wild West” (TV series: 1965–1969); “Wild Wild West” (movie: 1999)

“The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” (2003)

“Steamboy” (anime film: 2004)

“Sherlock Holmes” (2009)

“Warehouse 13” (TV series: 2009-)

Steampunk info/community on the web:

The Steampunk Empire: The Crossroads of the Aether, thesteampunkempire.com

Steampunk magazine, steampunkmagazine.com

“Steampunk fortnight” blog, tor.com/blogs/2010/10/steampunk-fortnight-on-torcom

The Steampunk Workshop, steampunkworkshop.com

Other resources:

computer/console games: Myst (1993); BioShock (2007)

Templecon convention (Feb 4-6, 2011; Warwick, RI), templecon.org

Steam & Cinders live-action role-playing game (Boston), be-epic.com

Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation (Waltham, MA), crmi.org (“Steampunk: Form and Function” exhibit through May 10; Steampunkers “meet up” Dec. 19; steampunk course March, 2011; New England Steampunk Festival April 30-May 1, 2011)

Steampuffin appliances and inventions and ModVic Victorian and steampunk home design (Sharon, MA), steampuffin.com, modvic.com

--- Ethan Gilsdorf

We all role-play now

[Note: Ethan Gilsdorf speaks at the Boston Public Library Wed, Oct 20. Other upcoming speaking engagements: Attleboro, MA: Oct. 29th (part of a Creature Double Feature tribute!); Brattleboro, VT: Nov 11th; Somerville, MA: Nov 13th; Cambridge, MA: Nov 15th; Providence, RI: Nov 18th; Burlington, MA: Nov 20th; Brooklyn, NY: Nov 22nd. More book tour info here]

We all role-play now

Those Dungeons & Dragons skills can come in handy in the world of Facebook

"The Social Network,'' Hollywood's latest box office king, charts Facebook's meteoric rise to near ubiquity. Few have not heard of the world-girdling website or been ensnared by its tendrils. In six years, Facebook has woven its way into the daily lives of some 500 million users.

Whether to check up on friends' exploits or play games like "Mafia Wars,'' we've grown accustomed to its promise of instant intimacy and, some might argue, its voyeuristic pleasures. Many cheer the way Facebook has democratized the flow of information; no longer top-down, news is now horizontally and virally dispersed. Others gripe that it's warped our idea of significance, making what I had for breakfast as important as the latest developments in the Mideast peace process. Facebook's vast and sticky web of connection has caused us all to re-evaluate what we mean by "friend.'' And, I suppose, "enemy'' as well.

Unforeseen social aftershocks such as these have rippled in Facebook's wake. Others have yet to be detected. But there's something else at work with Facebook. It's actually making role-players of us all.

Role-playing? Like that conflict-resolution exercise your sales team endured last year? Or role-playing, as in Dungeons & Dragons - that strange and wondrous game I (and perhaps you) played back in the Reagan administration, rolling dice in a basement and slaying goblins and dragons and snarfing bowls of Doritos?

Role-playing? Like that conflict-resolution exercise your sales team endured last year? Or role-playing, as in Dungeons & Dragons - that strange and wondrous game I (and perhaps you) played back in the Reagan administration, rolling dice in a basement and slaying goblins and dragons and snarfing bowls of Doritos?

I'd argue all these experiences - including posting a witty Facebook update - are cut from the same role-playing cloth. We all share that desire to be someone else. To be better, stronger, faster; to appear more handsome, more clever, more attractive than our fleshy selves might ever be. "My, aren't we having fun?'' say our photos, snapped while we're half drunk and posted in a day-after haze. On my Match.com profile, I offer clues that might seduce. I suggest, in a whisper of pixels, "I am your ideal man.''

Not that role-playing is devious. It's a necessary counter to the way we've been civilized. While hidden behind the screen, we give ourselves permission to behave more dauntless or brazen than we'd allow in real life. We get to practice being the best version of the person we can be, or want to be.

That said, some role-playing experiences, especially offline ones, are deemed more acceptable than others. Dressing up as Tom Brady and painting your body blue and red for the big game? That's OK. Dressing as Gandalf and wearing a purple wizard hat for the big game? Not so much. Even as World of Warcraft and D&D and Harry Potter fandom have become passable in many circles, adults raiding Mom's closet for goofy clothes for "make-believe'' still remains verboten.

Except, of course, at Halloween. This odd holdover from pagan times is a socially acceptable way to bust loose. Here, costumes are fine. And playing "bad'' is encouraged. Being Dracula or Nurse Hottie for an evening can be instructive, even liberating.

The irony here is that even in our pre-Facebook existences, we've always engaged in day-to-day role-playing. At a wedding or cocktail party, on a first date or during a job interview, or when home for the holidays, we all dress the part and adopt another character: Brilliant or Well Adjusted, Stockbroker or Salesman, Happy Son or Perfect Mom. If you're not willing to play along and put on a mask, friends (and potential employers) will think, "What's wrong? Come on, get into character.'' Life is a dungeon crawl, full of monsters and opportunities to be on your mettle. Be prepared. Chin up.

So here's the rub. Eventually, we have to live up to these personas we've created. Many a first date has witnessed the crumbling of expectation's towers and spires. And despite my hundreds of Facebook friends, I wonder who I can really count on in times of trouble. When I really do need to be brave and slay that dragon.

Ethan Gilsdorf is author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now in paperback. More info on Gilsdorf and the book here.

On the appeal of fantasy role-playing games

One of the author's D&D dungeon maps

One of the author's D&D dungeon maps

We craved adventure and escape.

When people ask if I played sports in high school back, I tell them I was on the varsity Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) team, starting quarterback, four years in a row. (I was also president of the A/V club. And I memorized Monty Python sketches. And learned BASIC computer programming.) For me, RPGs (role-playing games) like D&D were empowering and exciting, and a clever antidote to the anonymity, monotony, and clique warfare of high school. In lieu of keg parties or soccer practice to vent our angst, we had D&D night. Who needs sports stardom when you can shoot fireballs from your fingertips?

I played every week, sometimes twice a week, from eighth grade to senior year, Friday night from 5:00 p.m. until midnight. JP, my other neighborhood friend Mike, and I first played by ourselves, then found a peer group of other gamers: Bill K., Bill S., Bill C., Dean, Eric M., Eric H. and John. Some of us had endured plenty: my Mom had suffered a brainaneurysm and came home damaged goods; Eric H.’s mom had died, John’s dad had suffered a brain injury similar to my mom’s, and JP was born with a disease that caused brittle bones, cataracts, and stunted growth.

I think on some level we knew we didn’t fit in. Perhaps we were weird. Girls were scarce commodities for us, and our group may have proved that tired cliché that outcasts, dweebs, and computer nerds couldn’t handle reality, let alone get a date for the prom. But nothing stopped us from playing, and the popular kids didn’t really care one way or the other. We were left alone to our own devices: maps, dice, rule books, and soda. It didn’t take long before words like halberd and basilisk became part of my daily vocabulary. Like actors in a play, we role-played characters—human, Elvish, dwarven, halfling—who quickly became extensions of our better or more daring selves. We craved adventure and escape.

One of us would be the Dungeon Master (DM) for a few weeks or months. Games lasted that long. The DM was the theater director, the ref, the world-builder, the God. His preprepared maps and dungeons, stocked with monsters, riddles, and rewards, determined our path through dank tunnels and forbidding forests. Our real selves sat around a living room or basement table, scarfing down provisions like bowls of cheese doodles and generic-brand pizza. We outfitted our characters with broad- swords, battle-axes, grappling hooks, and gold pieces. “In game,” these characters memorized spells and collected treasure and magic items such as +2 long swords and Cloaks of Invisibility and Rods of Resurrection. Then, the adventure would begin. The DM would set the scene: often, we’d be a ragtag band of adventurers who’d met at the tavern and heard rumors of dungeons to explore and treasure to be had. Or some beast or sorcerer terrorizing the land needed to be slayed. Before too long, we’d enter some underground world to solve riddles, search for secret doors, and find hidden passages.

We parleyed with foes—goblins, trolls, harlots—and attacked only when necessary. Or, wantonly, just to taste the imagined pleasure of a rough blade running through evilflesh. We racked up experience points. We test-drove a fiery life of pseudo-heroism, physical combat, and meaningful death. Whatever place the DM described, as far as we were concerned, it existed. Suspended jointly in our minds, it was all real. We were bards, jesters, and storytellers. We told each other riddles in the dark.

And each dungeon level would lead to the next one even deeper beneath the surface, full of more dangerous monsters, and even harder to leave.

At Least There Was a Rulebook

The joy in the game was not simply the anything-can-happen fantasy setting and the killing and heroic deeds, but also the rules. Hundreds of rules existed for every situation. Geeks and nerds love rules. D&D (and its sequel, AD&D, or Advanced Dungeons & Dragons) let us traffic in specialized knowledge found only in hardbound books with names like Monster Manual and Dungeon Masters Guide. As we played, we consulted charts, indices, tables, descriptions of attributes, lists of spells, causes and effects—like a school unto itself, filled with answers to questions about the rarity of magic items, crossing terrain, and how to survive poison.

And we loved to fight over the minutiae. (Sample argument: Player: “What do you mean a gelatinous cube gets a plus on surprise?” DM: “It’s invisible.” Player: “But it’s a ten foot cube of Jello! Let me see that . . . .” Player grabs Monster Manual from DM. Twenty minute argument ensues.)

We could tell a mace from a morning star, a cudgel from a club, and we knew how to draw them. We knew a creature called a “wight” inflicted one to four hit points of damage when it attacked. Could we recharge wands? No. If I died, I could be resurrected, because, according to page 50 of the Players Hand- book, a ninth-level cleric could raise a person who had been dead for no longer than nine days. “Note that the body of the person must be whole, or otherwise missing parts will still be missing when the person is brought back to life.” All good stuff to know. The trolls and fireballs may be fanciful, but they have to behave according to a logical system.

Like in life, fantasy rules were affected by chance—the roll of the dice. And, as if they were jewels, we collected bags of them: plastic, polyhedral game dice, four-, six-, eight-, ten-, twelve-, and twenty-sided baubles that, like I Ching sticks or coins, foretold our fortunes when cast. A spinning die, such as the icosahedral “d20,” could land on “20” (“A hit! You slice the lizard man’s head off and green blood spurts everywhere!”) as often as “1” (“Miss! Your sword swings wide and you stab yourself. Loser!”).

The lesson? Real life thus far had taught me that in the adult world, fate was chaotic and uncertain. Guidelines for success were arbitrary. But in the world of D&D, at least there was a rule book. We knew what we needed to roll to succeed or survive. The finer points of its rules and the possibility of predicting outcomes offered comfort. Make-believe as they were, the skirmishes and puzzle-solving endemic to D&D had immediate and palpable consequences. By role-playing, we were in control, and our characters—be they thieves, magic-users, paladins, or druids—wandered through places of danger, their destinies, ostensibly, within our grasp.

At the same time, we understood that our characters’ failures and triumphs were decided by unknown forces, malevolent or kindly. Such was the double-edged quality of our fantasy life, where random cruelty or unexpected fortune ruled the day. The game was a risk-free milieu for doing adult things.

It was also a relief to live life in another skin, and act out behind the safety of pumped-up attributes. D&D characters had statistics in six key areas: strength, intelligence, wisdom, dexterity, constitution, and charisma. These ranged from three to eighteen. Ethan the real boy’s stats would have been all under 10; his fighter character Elloron’s were all sixteens, seventeens, and eighteens.

And who wouldn't want to be that?

[adpated from Ethan Gilsdorf's award-winning travel memoir and pop culture investigation Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now available in paperback. For more info, see: http://www.ethangilsdorf.com/]

The author's old, worn-out D&D dice

The author's old, worn-out D&D diceDungeons & Dragons Saved My Life

The author, circa 1982

The author, circa 1982

The summer before my eighth-grade year, when I was 12, I learned to escape.

This was 1979. My mother had been home from the hospital for a few months, and my sister, brother and I were still coming to understand the “new Mom.”

This new mother had survived a brain aneurysm. Her left side was mostly paralyzed, and she behaved strangely. Sometimes she scared me. We called her the Momster.

I couldn’t tame her, not this beast, and I knew I couldn’t save her, either. I was stuck with a mother I didn’t know how to love

But later that summer, something wondrous happened—I learned how to face my demons in another way. I learned that sometimes, checking out from reality was not just a fun diversion, but necessary for survival.

An article about that mysterious, possibly dangerous, new game fad D&D

An article about that mysterious, possibly dangerous, new game fad D&D

A new kid named JP had moved across the street from me. One hot August day, JP showed me a clever trick—how to step away from my own body and mind, my family, and travel to places I’d never even seen. A way out.

“Ever play D&D?” JP asked, standing in my kitchen, eyes bright and magnified behind his extra-thick glasses. He was quite short, frail-looking, but feisty and fast-talking.

“D&D?” I said. “What’s that—a board game?”

“Dungeons & Dragons? It’s not a normal board game. . . . See, you play a character. . . . There’s all these rules.” He rummaged through his backpack and pulled out a pile of books, then poured a sack of colorful objects onto the table. They looked like gemstones. “Check out these cool dice! See, I’m the Dungeon Master. I create a scenario, man adventure, a world. You tell me what your character wants to do.”

“Character? What do you mean?” I asked. This kid was weird.

Invented by two geeks in the Midwest, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, the was only five years old back in 1979. Few had ever played anything like this before. Born of a similar swords-and-scorcery, myth-laden backdrop as J.R.R. Tolkien's world of Middle-earth, D&D was a game where you got to take action, be the hero, go on a quest. The game taught social skills, leadership, and strategy; it inspired creativity and storytelling, and provided rites of passage, accomplishment and belonging, even belief systems. I didn't get it at the time, but D&D and its ilk let people safely try out aspects of their personalities --- often dark, evil sides, or extroverted or flirtatious --- they could not or would not flex in "real life." The games connected folks tomagical thinking, to nature, to a primal, pick-up-your-battle-ax and kill mentalities long suppressed by so-called society. All of which would later serve me well in life.

D&D would open up a universe of creative expression to shy, introverted, non-athletic kids like me who felt about as powerful as a three-foot hobbit on the basketball team.

But at the moment, I was confused. I had no idea how play.

JP sighed. “OK, it goes like this. Pretend you’re in a dark woods. Up ahead on the path, you see a nasty-looking creature: seven feet tall, pointy ears, mouth full of black rotten teeth. ‘Friend or foe?’ it grumbles. Its fist tightens on the morning star in his hand, and it begins to heft it. Like this.” JP grabbed a frying pan off the stove. He swung it in the air. “What do you do?”

“What do I do?”

“It’s an orc. What do you want to do?”

“Uh . . . ” I stalled. What is going on? I thought. I didn’t even know what a morning star was. Or an orc.

"What are you going to do?" JP asked again, a little more impatiently.

“Uh, I’ll attack? With my sword. Do I have a sword?”

JP rolled the dice and squinted at a rulebook. “OK, your short sword strikes its shoulder. Black blood spurts out. It screams, ‘Arrghhh!’ You whack it for four hit points.”

“Cool.” I wanted to ask what a “hit point” was, but it didn’t matter. My anxiety, my weird home life, my mother’s limp, all of it began to fade. I was hooked. I didn’t know it at the time, but Dungeons & Dragons was about to save my life.

“Now the orc comes charging at you. He’s really mad.” JP bared his teeth for effect. “Now what do you do?” he asked, a big grin spreading across his face.

What do I do? I was 12. It was 1979. I had just discovered the power of escape, and vicarious derring-do. Later, I would learn much more about orcs and morning stars and a universe of wondrous things. There was so much I wanted to do.

Who needs varsity sports when you can be a wizard and shoot fireballs from your fingertips?

Adapted from the Prologue to Ethan Gilsdorf's travel memoir and pop culture investigation Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now in paperback. More info:http://www.ethangilsdorf.com

Adapted from the Prologue to Ethan Gilsdorf's travel memoir and pop culture investigation Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now in paperback. More info:http://www.ethangilsdorf.com

A virtual world that breaks real barriers

Rose Springvale is the avatar of Georgiana Nelsen, who cofounded Al-Andalus, a virtual world patterned after medieval Andalus in Spain, where Christians, Jews, and Muslims coexisted harmoniously under Islamic rule. [Courtesy of Rita King and Joshua Fouts]In Second Life's Al-Andalus, a virtual world patterned after medieval Andalus in Spain, avatars of Muslims mix with avatars of Jews and Christians to strive for a more perfect union.

Rose Springvale is the avatar of Georgiana Nelsen, who cofounded Al-Andalus, a virtual world patterned after medieval Andalus in Spain, where Christians, Jews, and Muslims coexisted harmoniously under Islamic rule. [Courtesy of Rita King and Joshua Fouts]In Second Life's Al-Andalus, a virtual world patterned after medieval Andalus in Spain, avatars of Muslims mix with avatars of Jews and Christians to strive for a more perfect union.[from Ethan Gilsdorf's article in the Christian Science Monitor]

Thus far in the relatively short existence of online worlds and virtual communities, less than flattering stories typically float to the surface. The Internet is rife with tales of bad behavior: antisocial "trolls" posting inflammatory messages; players addicted to fantasy role-playing games; and marriages ruined by spouses staying up half the night to flirt in virtual spaces, even proposing marriage to people they've never met in the flesh.

Given the power of negative thinking, it's worth repeating: Not all that happens within the digital realms of monsters, quests, and virtual dollars is evil. Much of the zombie-shooting amounts to people having fun or finding an escape. But some online communities embrace a more lofty mission. They're forging new relationships across the chasms of nationality, religion, and language – long the unrealized dream of some who hoped the Internet could bring us closer.

One such place is Al-Andalus, named after a real nation that once existed in the Iberian Peninsula. From the 8th to the 15th centuries, the spirit of la convivencia, "coexistence," ruled Spain. Christians, Muslims, and Jews lived together mostly harmoniously, and created a vibrant artistic, scientific, and intellectual community.

The volunteers who "built" Al-Andalus in Second Life, the virtual world created by company Linden Lab, wanted to re-create that utopian place, particularly in the wake of the intercultural ill will brewing since 9/11. Only their Al-Andalus is made of pixels, not bricks, and peopled not by humans but their digital doppelgängers, or avatars.

"I'm a pacifist. I'm a mother," says cofounder Georgiana Nelsen, a business lawyer practicing in Houston who in Second Life (SL) goes by "Rose Springvale" (and, informally, the "Sultana"). "I want to always teach 'Use your words, not your hands.' And so this appealed to my personal desire to do something positive in the world rather than continue to foster things that are divisive."

After nine months of construction, Al-Andalus opened its virtual doors in July 2007, and now has 350 contributing members and receives thousands of day-trippers. The democratically run community (and recognized nonprofit) is roughly one-quarter Jewish, one-quarter Muslim, and the remainder Christian and atheist. The massive virtual grounds include a re-creation of the Alhambra and Alcázar fortresses and palaces and the Great Mosque of Córdoba, plus a caravan market, library (run by a Smithsonian librarian), theater, and art center. People can attend a flamenco concert; a meeting; or a religious service in a synagogue, church, or mosque – or even ride a magic carpet for an aerial tour (almost 180,000 have done so).

Read the rest here at the Christian Science Monitor

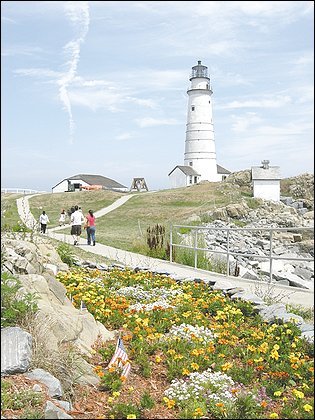

Impulsive Traveler: Boston's Harbor Islands shelter a multitude of surprises

In the ominous opening of Martin Scorsese's movie "Shutter Island," Leonardo DiCaprio and Mark Ruffalo, playing federal agents, take a boat out to a craggy-cliffed island off the coast of Boston.

In the ominous opening of Martin Scorsese's movie "Shutter Island," Leonardo DiCaprio and Mark Ruffalo, playing federal agents, take a boat out to a craggy-cliffed island off the coast of Boston.

"My friends were watching the DVD and said, 'Wow! You have an island like that?' " said Phil Rahaim, a park ranger on the Boston Harbor Islands. He had to tell them, "Not exactly."

"Shutter Island" was partly shot on an island called Peddocks, but none of the 34 real harbor islands actually look much like the movie's CG-enhanced slab of rock. Nor have any of them ever housed an insane asylum conducting experiments with psychotropic drugs.

Geek Out!

Like when the planets align, there are a few times each year when geeks can fly their freak flags high and proud, in vast numbers, and at the same time in different parts of the universe.

Like when the planets align, there are a few times each year when geeks can fly their freak flags high and proud, in vast numbers, and at the same time in different parts of the universe.

This coming Labor Day is one of those weekends.

On the west coast, we have Pax, in Seattle, a three-day game festival for tabletop, videogame, and PC gamers and a general celebration of gamer-geek culture. (And in the other corner, Atlanta, we have Dragon*Con. But more on that another time.)

In fact, Pax calls itself a festival and not a convention because in addition to dedicated tournaments and freeplay areas (The east coast version in Boston this spring had a very cool classic arcade game room, which was amazing! All your fave games like Frogger, Galaga and my fave, Robotron 2084), they’ve got nerdcore concerts from awesome performers like MC Frontalot and Paul & Storm, panel discussions like “The Myth of the Gamer Girl,” the Omegathon event (A three-day elimination tournament in games from every category, from Pong toHalo to skeeball), and an exhibitor hall filled with booths displaying the latest from top game publishers and developers.

But I was thinking that probably the best part of PAX (and similar events like Dragon*Con, the other big fantasy/science fiction fandom event of the year) is this: You get to hang out with kindred folk who love their games and books and movies and costumes. They will argue and defend their fandom universes to the death. They will argue why Tom Bombadil should not have been cut from Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. They will battle over Kirk vs. Picard. They will annoy and astound you with their detailed, persnickety knowledge.

In other words, a geek is less what someone loves as it is HOW they love that object of affection. Geeks are passionate about their thang before it became fashionable and long after it’s passed from the public eye. Perhaps that’s the best definition of a geek.

If you’re headed to Atlanta or Seattle this weekend, check here for how to win a free copy of my book Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks, now out in paperback.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of the award-winning travel memoir-pop culture investigation Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now out in paperback. You can reach him and get more information at his website www.ethangilsdorf.com.

When literary authors slum in genre

There’s a curious phenomenon happening out there in LiteraryLand: The territory of genre fiction is being invaded by the literary camp.

There’s a curious phenomenon happening out there in LiteraryLand: The territory of genre fiction is being invaded by the literary camp.

While it could be argued that literary writers have always borrowed from fantasy, science fiction and horror, even stolen genre's best ideas, I think there's a new and significant shift happening in the past few years.

Take Justin Cronin, writer of respectable stories, who recently leaped the chasm to the dystopian, undead-ridden realm of Twilight. With The Passage, his post-apocalyptic, doorstopper of a saga, the author enters a new universe, seemingly snubbing his former life writing “serious books” like Mary and O’Neil and The Summer Guest, which won prizes like Pen/Hemingway Award, the Whiting Writer’s Award and the Stephen Crane Prize. Both books of fiction situate themselves solidly in the camp of literary fiction. They’re set on the planet Earth we know and love. Not so with The Passage, in which mutant vampire-like creatures ravage a post-apocalyptic U.S. of A. Think Cormac McCarthy’s The Road crossed with the movie The Road Warrior, with the psychological tonnage of John Fowles’ The Magus and the “huh?” ofThe Matrix.

Now comes Ricky Moody, whose ironic novels like The Ice Storm andPurple America were solidly in the literary camp, telling us about life in a more-or-less recognizable world. His latest novel, The Four Fingers of Death, is a big departure, blending a B-movie classic with a dark future world. The plot: A doomed U.S. space mission to Mars and a subsequent accidental release of deadly bacteria picked up on the Red Planet results in that astronaut’s severed arm surviving re-entry to earth, and reanimating to embark on a wanton rampage of strangulation.

And there’s probably other examples I’m forgetting at the moment.

So what’s all this forsaking of one’s literary pedigree about?

It began with the flipside of this equation. It used to be that genre writers had to claw their way up the ivory tower in order to be recognized by the literary tastemakers. Clearly, that’s shifted, as more and more fantasy, science fiction, and horror writers have been accepted by the mainstream and given their overdue lit cred. It’s been a hard row to hoe. J.R.R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Philip Pullman and others helped blaze the trail to acceptance. Now these authors have been largely accepted into the canon. You can take university courses on fantasy literature and write dissertations on the homoerotic subtext simmering between Frodo and Sam. A whole generation, now of age and in college, grew up reading (or having read to them) the entire oeuvre of Harry Potter. That’s a sea change in the way fantasy will be seen in the future—not as some freaky subculture, but as widespread mass culture.

Yes, Margaret Atwood and Doris Lessing have delved into genre, although their works (A Handmaid's Tale, for example) was always taken as highbrow. Perhaps a better example: Stephen King, considered a hack horror writer for years who began publishing in the New Yorker in 1990. One wonders why the New Yorker finally caved and let him in the doors --- is this an implicit acknowledgement of his popularity? Or had King's writing gotten better. In any case, it's was a shocker when he began racking up impressive literary kudos, like in 2003 when the National Book Awards handed over its annual medal for distinguished contribution to American letters to King. Recently in May, the Los Angeles Public Library gave its Literary Award for his monstrous contribution to literature.

Now, as muggles and Mordor have entered the popular lexicon, the glitterati of literary fiction find themselves “slumming” in the darker, fouler waters of genre. (One reason: It’s probably more fun to write.) But in the end, I think it’s all about call and response. Readers want richer, more complex and more imaginative and immersive stories. Writers want an audience, and that audience increasingly reads genre. Each side—literary and genre—leeches off the other. The two camps have more or less met in the middle.

One wonders who’s going to delve into the dark waters next—Philip Roth? Salman Rushdie? Toni Morrison? Actually, it turns they already (sort of) have --- Roth explores alternative history in The Plot Against America;

Rushdie's "Magical Realism," of Midnight's Children, in which children have superpowers. You might even argue that Morrison's Beloved is a ghost story.

[thanks to readers at Tor.com, where this post originally appeared, for catching some errors and helping me revise this into a better essay]

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, which comes out in paperback in September. Contact him through his website,www.ethangilsdorf.com

Pixels of the Past

Pong, Space Invaders, Galaga, Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, Dig Dug, Joust, Centipede, Tron, Dragon's Lair, and my personal favorite, Robotron 2084.

Pong, Space Invaders, Galaga, Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, Dig Dug, Joust, Centipede, Tron, Dragon's Lair, and my personal favorite, Robotron 2084.

If you're a 30- or 40-something geek like me, you probably played video games as a kid. Not on the personal computer, which in the 70s and 80s was only in its infancy. I mean the big, hulking, stand-up video arcade machines. The ones that ate your allowance (or cafeteria milk money).

As I write about in the my recent article for the Christian Science Monitor "Video game museum gives arcade classics extra lives" (print edition archived here), these games have had a powerful effect on an entire generation. And now that generation is all grown up, like with a lot of childhood or adolescent hobbies looked back on with the 20-20 hindsight of adulthood, these old school arcade games create nostalgia. We have money, we have desire, and we want our childhoods back. If you have kids of your own, that's another reason to dip into the days of 8-bit pixels and dim, humming, cave-like video arcades. The ones near my hometown were called The Space Center and The Dream Machine. Cool.

When generations reach middle age, there's a curious phenomenon: a nostalgia for the way things were kicks in. For me, the "way" was that pre-Mac, pre-iPhone, pre-iPod, pre-Internet world where people called each other on payphones and left notes in each other's lockers to communicate, made plans ahead of time, and had to meet in public, in person (gasp!) in order to play a video game. None of this hunkering down for hours at a time to immerse oneself in online games; these games of yore, like say Missile Command or cost a quarter or fifty cents, and for me anyway, they lasted about 10 minutes tops. The little Pac-Man or Space Invader was iconic, symbolic, crude. It was like a metaphor for a little you.

The draw of old video games, like old anything, is a desire feel closer to a unspoiled experience. As Henry Lowood says in my article, video game game nostalgia is about "stripping away the surface layers associated with modern games gives them the feeling of being closer to something we might call core game-play." Modern games are inordinately complex and require the mastery of bunches of buttons. The arcade game had maybe two or three buttons and a joystick. Sometimes just a joystick ---- a cave man bone tool compared to games like Gears of War or World of Warcraft.

We want to be connected to that time when things were, yep, simpler. When we didn't have all these fancy 3D computer animation technologies that produced photorealistic environments. When you could register your initials on the top score list of your favorite game, and enjoy a moment of fame ... until the next person came along to knock you off the leader board.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, which comes out in paperback in September. Contact him through his website, www.ethangilsdorf.com.

Real-Life Role-Playing

Real-Life Role-Playing

When Max Delaney came to rural Maine 13 years ago, his itinerant family moved from town to town, school to school. With few social connections, he felt isolated. Like an outsider.

When Max Delaney came to rural Maine 13 years ago, his itinerant family moved from town to town, school to school. With few social connections, he felt isolated. Like an outsider.

"It was hard for me to find people," says Mr. Delaney, now 21. "I was searching for a community." His academic performance suffered, and he didn't get along with his teachers. "I did not do well with authority in school."

Then, the year his family arrived in Belfast, a coastal town of some 6,300 on Penobscot Bay, he discovered The Game Loft and finally found his tribe.

Similar to other youth-development organizations such as Outward Bound or Scouting, The Game Loft also fosters risk-taking, leadership, and camarad erie. But for kids who find the football gridiron to be a foreign world, The Game Loft immerses them in a different sort of team sport.

Via table-top role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), Game Loft members play characters armed not with football padding and hockey sticks but chain mail, broadswords, light sabers, and magic spells. Working together, they charge onto battlefields and explore underground dungeons, seeking valor in these imaginary realms.

"I took to [role-playing] immediately," Delaney says. He joined as a member of The Game Loft, then started volunteering as a staff member, and finally became an employee. Along the way, the games he played built up his character in the real world.

"Killing dragons is a challenge," says Ray Esta brook, The Game Loft's codirector and cofounder. His center connects dragon-slaying to the challenges life throws at you. Via gaming, kids test out "roles," but in a safe, nonschool environment, in order to become functioning adults in society – connected, compassionate, and caring. "Good things happen to kids who game," he says.

Cofounder Ray Estabrook (standing) leads gamers in playing '1968: Gone but Not Forgotten,' a game he and his wife and co-founder Patricia created.

Cofounder Ray Estabrook (standing) leads gamers in playing '1968: Gone but Not Forgotten,' a game he and his wife and co-founder Patricia created.

"I was [at The Game Loft] to socialize with kids who had mutual interest not only in games but conversation," Delaney says. "It was a place to channel a lot of curiosity." Moreover, he was able to interact with kids of all ages, as well as adults, who treated him as an equal. "The level of respect we got at The Game Loft was different than [at] school."

The Game Loft addresses another concern: the proliferation of video games. In an age when parents worry about the potentially isolating and addictive effects of computer and console-based games such as World of Warcraft and Halo, The Game Loft offers an antidote. No electronic games are allowed within its doors. Rather, kids play games