Memoir Recounts Youthful Quest for Meaning in D&D, Comics, Zeppelin

Growing up in the suburbs of Boston, and raised on secular Judaism, Cocoa Puffs and Gilligan’s Island, Peter Bebergal found himself on a quest. A spiritual quest that, as a teen, led him through comic books, Dungeons & Dragons and Carlos Castaneda, with stops in the world of hallucinogens, rock ‘n’ roll, and occultism. All were attempts to find a deeper, more meaningful path to personal illumination.

Growing up in the suburbs of Boston, and raised on secular Judaism, Cocoa Puffs and Gilligan’s Island, Peter Bebergal found himself on a quest. A spiritual quest that, as a teen, led him through comic books, Dungeons & Dragons and Carlos Castaneda, with stops in the world of hallucinogens, rock ‘n’ roll, and occultism. All were attempts to find a deeper, more meaningful path to personal illumination.

Bebergal’s new coming of age memoir, Too Much to Dream: A Psychedelic American Boyhood (Soft Skull Press) recounts that journey, using his own story and extensive research to explore the connections among popular culture, drugs, religion, and the craving for spirituality that America’s youth seeks, but rarely finds.

Bebergal is the also co-author of The Faith Between Us. He studied religion at Brandeis and Harvard Divinity School and writes frequently on the intersection of popular culture, religion, and science as well as reviews on science fiction and fantasy. Some of his essays and stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Tin House, Times Literary Supplement, Tablet Magazine, The Revealer, and The Believer. He lives in Cambridge, Mass., with his wife and son.

I had a chance to ask Peter Bebergal some questions — as well as happily geek-out on ’70s pop culture, D&D, Led Zeppelin and … wait for it … Freakies cereal.

Ethan Gilsdorf: Peter, why did you decide to write the book?

Peter Bebergal: At the age of 40, sober for many years, I found myself collecting psychedelic music again and reading counterculture/fringe spiritual texts, digging through the bins of underground comics at Million Year Picnic in Harvard Square. I realized that all these years later I was still drawn to this world. At the same time I started investigating and writing on the recent upsurge of psychedelic drug research and the burgeoning psychedelic subculture. I started to ask myself why my experiences led to where they had and despite them, why I still loved these ideas, this music, and these stories. I decided to investigate my own life and try to get beyond the traditional memoir by looking at myself as part of a particular cultural moment, the post ’60s generation who grew up in the shadow of that time.

Gilsdorf: What was so unique about the era of your coming-of-age?

Bebergal: The mid to late ’70s was a time of incredibly weird and wonderful fringe pop culture. You could buy ESP cards at any bookstore, Creepy and Eerie Magazine were part of a revival of horror and supernatural comics, In Search Of and books on UFOs were commonplace, but the undercurrent was a kind of spiritual dissociation. The Aquarian age never happened, but the doors of altered consciousness had been opened. There was no looking back. I began to understand how my own story was part of a much larger cultural moment. I was symptomatic of a kind of Phillip-K-Dickian-post ’60s spiritual schizophrenia.

Bebergal: The mid to late ’70s was a time of incredibly weird and wonderful fringe pop culture. You could buy ESP cards at any bookstore, Creepy and Eerie Magazine were part of a revival of horror and supernatural comics, In Search Of and books on UFOs were commonplace, but the undercurrent was a kind of spiritual dissociation. The Aquarian age never happened, but the doors of altered consciousness had been opened. There was no looking back. I began to understand how my own story was part of a much larger cultural moment. I was symptomatic of a kind of Phillip-K-Dickian-post ’60s spiritual schizophrenia.

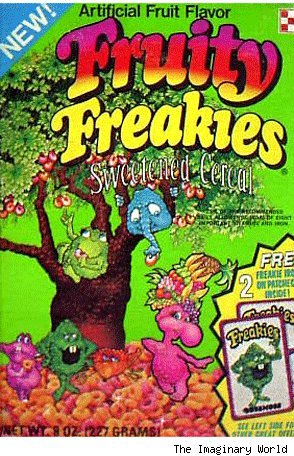

Gilsdorf: As a kid also growing up in the same era, I remember being haunted by Leonard Nimoy’s In Search Of TV series, as well as devouring books about the Loch Ness monster and Bigfoot. There are tons of examples of the weird and occult breaking through in the ’70s to the mainstream, aren’t there? Think of the X-Ray Vision glasses you could order from the back of a comic book, or plans to build your own hovercraft, or spy cameras, ventriloquist dummies, all kinds of tricks and magic. Remember Freakies breakfast cereal? All about a post-hippie commune of misfit toys who lived in a tree. What was that about?

Bebergal: Freakies cereal is an amazing example of the fringe making it into the mainstream. But it was so giddily counterculture, almost like a hippie practical joke, and yet it seemed to have this deep mythology, replete with individual characters with their own personalities, and even the great mythic trope, a world tree where all the Freakies gathered. I had to have it! I recall it was hard to find though, and that it actually tasted kind of horrible, but they came with a terrific prize, a magnet in the likeness of one of the characters.

Gilsdorf: Yes, even to be a “freak” was celebrated, and money was to be made from that. I saved up whatever it was, 17 proofs of purchase from Freakies cereal boxes, to get my own “Snorkeldorf” T-shirt. There was a kind of vast commercialization of the unknown, of the weird and the unexplained. Big change from the 1960s, huh?

Gilsdorf: Yes, even to be a “freak” was celebrated, and money was to be made from that. I saved up whatever it was, 17 proofs of purchase from Freakies cereal boxes, to get my own “Snorkeldorf” T-shirt. There was a kind of vast commercialization of the unknown, of the weird and the unexplained. Big change from the 1960s, huh?

Bebergal: The end of the 1960s was the end of a grand narrative, one that was both political and spiritual, and that spoke to a young person’s rebellious instincts. By the 1970s all the ideas of the ’60s were now part of the popular imagination, and lost their edge, could no longer inspire the next generation in the same way, and church/temple hadn’t changed since the hippies showed the emperor had no clothes.

Gilsdorf: So where did one go from there, in the wake of this disillusionment?

Begergal: Many like myself turned to more fantastical narratives to fill the void. Marvel Comics, for example, contained an entire fully imagined universe. Characters from one comic appeared as guest stars in others, and their lives were linked by not only common cause, but by familial relationships, and strange genetic connections and mystical connections. The complex and cosmic Marvel Universe was all about the connections between one hero and another. I was obsessed with the Magneto/Wanda/Quicksilver family tree that also, inexplicably, involved the High Evolutionary [Editor's note: I didn't know who High Evolutionary was; turns out he's a superhero with extrasensory powers of clairvoyance, cosmic awareness and astral projection, among others. -- E.G.]

Gilsdorf: Somehow I missed drinking the superhero comic Kool-Aid. But I discovered D&D big-time. In Too Much to Dream, you talk about the connection between D&D and fantasy fiction and then the occult and psychedelics in your life. Can you explain it here?

Bebergal: I think D&D was the perfect early antidote to what had been an entire childhood filled with magical thinking and a kind of spiritual unease. D&D gave me a healthy channel to express these abstract feelings. It was a concrete manifestation of the imagination, but it had rules and structure. When I started reading the books about psychedelic experiences written in the ’60s, they were as wondrous and exciting as any D&D game or Silver Surfer comic, but they spoke to that deeper existential need. I put down my maps and rule books and picked up sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll.

Bebergal: I think D&D was the perfect early antidote to what had been an entire childhood filled with magical thinking and a kind of spiritual unease. D&D gave me a healthy channel to express these abstract feelings. It was a concrete manifestation of the imagination, but it had rules and structure. When I started reading the books about psychedelic experiences written in the ’60s, they were as wondrous and exciting as any D&D game or Silver Surfer comic, but they spoke to that deeper existential need. I put down my maps and rule books and picked up sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll.

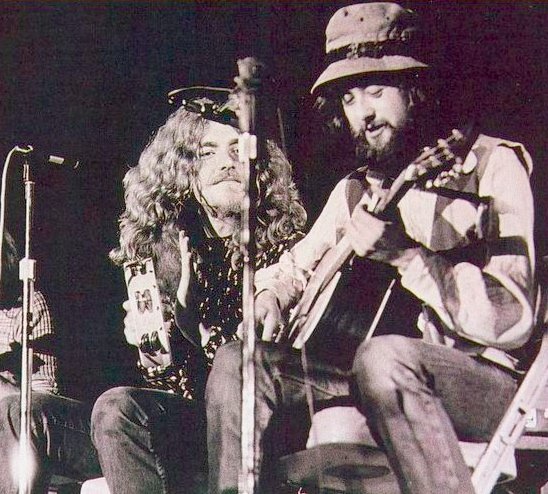

Gilsdorf: Being a huge Led Zeppelin fan, I have to ask: Where does Tolkien and Zeppelin fit into all this?

Gilsdorf: Being a huge Led Zeppelin fan, I have to ask: Where does Tolkien and Zeppelin fit into all this?

Bebergal: In the ’60s and ’70s there was a resurgent interest in Tolkien. Publishers put out encyclopedias of his world, linking the books to this vast mythology that by the sheer immensity of detail felt somehow real and maybe even a little “true.” This is what happens to the richest kinds myths, how they take on a quality of truth. Even Led Zeppelin sang about Mordor as if it was place they had visited and returned from. And for all of this, the new phenomena of role-playing gave you the tools to act out these stories, to create new worlds drawing from Tolkien, comics, even rock ‘n’ roll music.

Gilsdorf: I love that idea that, in their music, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page were essentially role-playing characters who had gone on an adventure in Middle-earth, interacting with Black Riders and Gollum. Great concept. Any other musicians that did this? Styx? Kansas? Blue Oyster Cult?

Bebergal: That era was a wonderland of rock as hero quest. Styx sang about a great voyage by sea that turns into a journey into space, Kansas wrote about sky gods, prophecy and mystical insight, and my personal favorite Rush’s Farewell to Kings was an entire fantasy epic that ends with a journey into a black hole. And then of course there is the great 1970s science fiction band Hawkwind, who collaborated with and were inspired by Michael Moorcock.

Gilsdorf: What do you think makes some people look for meaning so desperately they are driven to the point of madness?

Bebergal: It starts with what is a fundamental part of the human experience. Religion and myth are attempts to contain this pursuit, to give it some symbols and ritual, to give it language. But for some people, the more structure you try to impose, the more they see it as an empty gesture, that God or whatever you want to call it cannot be contained by any hierarchy or imposed regulations. Occult or esoteric traditions are attempts to get beyond conventional wisdom to something more experiential, but in the modern world, they have become bound up with every kind of paranormal and fringe idea. Go into any New Age bookstore and conspiracy theories about Freemasons are on the shelf below Aleister Crowley, right next to the books on UFOs. Of course it can weigh you down. I have come to love this stuff with a bit more critical distance these days.

Gilsdorf: Have you ever thought, OK, all this spiritual stuff makes some sense, but maybe I just liked getting high?

Bebergal: This is, in many ways, the central question. There is no doubt that at the bottom of all this is my drug addiction. It ruled me for sure. But like all things, it too did not exist in a vacuum. All the expectations I had for what these substances would do for me were intimately tied into all things that drove my psychology; Fantastic Four comic books, the writings of Timothy Leary, the music of Pink Floyd. My expectations could never be met. I would always be let down, and therefore always be looking for the next high. At some point, though, that is all there was.

Gilsdorf: To me it seems geek culture — sci-fi, fantasy, gaming, etc. – is increasingly replacing traditional culture (church, parents, government, community) as a source of moral or spiritual guidance to a whole generation of folks. Think of the wisdom received not from priests but Yoda and Gandalf. Can you comment as to why this phenomenon exists?

Bebergal: I think that there is this amazing intersection between geek culture and Wiccan/pagan communities. Even geeks need spirituality, but continue to turn to non-traditional places to find it. These traditions also speak, of course, to an interest in the fictional worlds of magic and old gods, etc.

Gilsdorf: What lessons do we learn from geek culture?

Bebergal: I seek the divine now in more mundane places; playing Legos and Minecraft with my son, watching a heron take flight from an inlet on the Charles River, looking at Saturn’s rings and moons through a telescope, listening to John Coltrane.

Gilsdorf: What about gaming. Have you returned to the fold?

Bebegal: The truth is, I am playing D&D again these days, another attempt to recapture some of that adolescent adventure without the drugs. But never, I must say, without the rock ‘n’ roll!

Gilsdorf: Yes, and rocking out to Zeppelin, I hope. “So I’ve decided what I’m gonna do now | So I’m packing my bags for the Misty Mountains | Where the spirits go now, | Over the hills where the spirits fly | I really don’t know.” I’ll pack my bags too, and see you in Middle-earth.

For more information about Bebergal and his book Too Much To Dream, visit toomuchtodream.net.

Bebergal: I think the best recent example of this is the comic Hellboy, a devil spawn struggling to maintain his humanity and his goodness. His is the great lesson that we are more than our genes, more than our destiny even, be it familial, cultural, political. Most recently he had to sacrifice himself to save the earth. Pro sports and American Idol cannot tell this story. Only a comic book on cheap newsprint somehow has access to the deepest layers of myth and can make them modern and relevant.

Gilsdorf: Do you still crave mystical experiences? How do you access them?

Bebergal: At first I was worried any mystical search would lead me back to the self-destruction, but despite myself, in the years past I have had deep spiritual experiences. They did not singe the hair off my head, but they were profound and have been a reminder that our normal waking consciousness is capable of experiencing so much more. Whether or not psychedelic drugs are a positive catalyst for this, I cannot say. Some people, particularly those ingrained in traditions that use them as part of their religious rituals (the Native American Church for example), have found deep spiritual significance with them. All I know for sure is that they are not meant for me.

Gilsdorf: So where do you seek safer transcendental moments?