Best games against social isolation

I was asked by the Boston Globe to recommend my favorite games --- board and card games, charades-type games, and role-playing games --- to play in person with your quarantine crew or online via video conference. In the story, I recommend Cards against Humanity, Dungeons & Dragons, and Pandemic.

Here are some of my picks that didn't make it into the story:

Here's the full story.

Let's get virtual... virtual ...

In which I try out a virtual reality exercise bike, become a pegasus, lasso some bandits, and come in second as a dog driving a Formula One racing car. Plus, I burn some calories. My story for the Boston Globe.

Computer games can save your life

All part of the NYTBR's coverage of nerdy/comics/gaming books.

Violent Video Games Are Good for You

[upcoming events with Ethan Gilsdorf: NYC/Brooklyn 11/22 (panel "Of Wizards and Wookiees" with Tony Pacitti, author of My Best Friend is a Wookiee); Providence, RI: 12/2 (also with Pacitti); and Boston (Newtonville 11/21 and Burlington 12/11) More info ...]

Violent Video Games Are Good for You

Rock and roll music? Bad for you. Comic books? They promote deviant behavior. Rap music? Dangerous.

Rock and roll music? Bad for you. Comic books? They promote deviant behavior. Rap music? Dangerous.

Ditto for the Internet, heavy metal and role-playing games. All were feared when they first arrived. Each in its own way was supposed to corrupt the youth of America.

It’s hard to believe today, but way back in the late 19th century, even the widespread use of the telephone was deemed a social threat. The telephone would encourage unhealthy gossip, critics said. It would disrupt and distract us. In one of the more inventive fears, the telephone would burst our private bubbles of happiness by bringing bad news.

Suffice it to say, a cloud of mistrust tends to hang over any new and misunderstood cultural phenomena. We often demonize that which the younger generation embraces, especially if it’s gory or sexual, or seems to glorify violence.

The cycle has repeated again with video games. A five-year legal battle over whether violent video games are protected as “free speech” reached the Supreme Court earlier this month, when the justices heard arguments in Schwarzenegger v. Entertainment Merchants.

Back in 2005, the state of California passed a law that forbade the sale of violent video games to those younger than 18. In particular, the law objected to games “in which the range of options available to a player includes killing, maiming, dismembering or sexually assaulting an image of a human being” in a “patently offensive way” — as opposed to games that depict death or violence more abstractly.

But that law was deemed unconstitutional, and now arguments pro and con have made their way to the biggest, baddest court in the land.

In addition to the First Amendment free speech question, the justices are considering whether the state must prove “a direct causal link between violent video games and physical and psychological harm to minors” before it prohibits their sale to those under 18.

So now we get the amusing scene of Justice Samuel Alito wondering “what James Madison [would have] thought about video games,” and Chief Justice John Roberts describing the nitty-gritty of Postal 2, one of the more extreme first-person shooter games. Among other depravities, Postal 2 allows the player to “go postal” and kill and humiliate in-game characters in a variety of creative ways: by setting them on fire, by urinating on them once they’ve been immobilized by a stun gun, or by using their heads to play “fetch” with dogs. You get the idea.

This is undoubtedly a gross-out experience. The game is offensive to many. I’m not particularly inclined to play it. But it is, after all, only a game.

Like with comic books, like with rap music, 99.9 percent of kids — and adults, for that matter — understand what is real violence and what is a representation of violence. According to a report issued by the Minister of Public Works and Government Services in Canada, by the time kids reach elementary school they can recognize motivations and consequences of characters’ actions. Kids aren’t going around chucking pitchforks at babies just because we see this in a realistic game.

And a strong argument can be made that watching, playing and participating in activities that depict cruelty or bloodshed are therapeutic. We see the violence on the page or screen and this helps us understand death. We can face what it might mean to do evil deeds. But we don’t become evil ourselves. As Gerard Jones, author of “Killing Monsters: Why Children Need Fantasy, Super Heroes, and Make-Believe Violence,” writes, “Through immersion in imaginary combat and identification with a violent protagonist, children engage the rage they’ve stifled . . . and become more capable of utilizing it against life’s challenges.”

Sadly, this doesn’t prevent lazy journalists from often including in their news reports the detail that suspected killers played a game like Grand Theft Auto. Because the graphic violence of some games is objectionable to many, it’s easy to imagine a cause and effect. As it turns out, a U.S. Secret Service study found that only one in eight of Columbine/Virginia Tech-type school shooters showed any interest in violent video games. And a U.S. surgeon general’s report found that mental stability and the quality of home life — not media exposure — were the relevant factors in violent acts committed by kids.

Besides, so-called dangerous influences have always been with us. As Justice Antonin Scalia rightly noted during the debate, Grimm’s Fairy Tales are extremely graphic in their depiction of brutality. How many huntsmen cut out the hearts of boars or princes, which were then eaten by wicked queens? How many children were nearly burned alive? Disney whitewashed Grimm, but take a read of the original, nastier stories. They pulled no punches.

Because gamers take an active role in the carnage — they hold the gun, so to speak —some might argue that video games might be more affecting or disturbing than literature (or music or television). Yet, told around the fire, gruesome folk tales probably had the same imaginative impact on the minds of innocent 18th century German kiddies as today’s youth playing gore-fests like “Left 4 Dead.” Which is to say, stories were exciting, scary and got the adrenaline flowing.

Another reason to doubt the gaming industry’s power to corrupt: More than one generation, mine included, has now been raised on violent video games. But there’s no credible proof that a higher proportion of sociopaths or snipers roams the streets than at any previous time in modern history. In fact, according to Lawrence Kutner and Cheryl K. Olson, founders of the Center for Mental Health and Media (a division of the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Psychiatry), and members of the psychiatry faculty at Harvard Medical School, as video game usage has skyrocketed in the past two decades, the rate of juvenile crime has actually fallen.

Children have always been drawn to the disgusting. Even if the ban on violent games is eventually deemed lawful and enforced in California, the games will still find their way into the hot little hands of minors. So do online porn, and cigarettes and beer. But these vices haven’t toppled Western civilization.

Not yet, anyway — although a zombie invasion or hurtling meteor might. Luckily, if you’re a good enough gamer, you’ll probably save the day.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now in paperback.

Real-Life Role-Playing

Real-Life Role-Playing

When Max Delaney came to rural Maine 13 years ago, his itinerant family moved from town to town, school to school. With few social connections, he felt isolated. Like an outsider.

When Max Delaney came to rural Maine 13 years ago, his itinerant family moved from town to town, school to school. With few social connections, he felt isolated. Like an outsider.

"It was hard for me to find people," says Mr. Delaney, now 21. "I was searching for a community." His academic performance suffered, and he didn't get along with his teachers. "I did not do well with authority in school."

Then, the year his family arrived in Belfast, a coastal town of some 6,300 on Penobscot Bay, he discovered The Game Loft and finally found his tribe.

Similar to other youth-development organizations such as Outward Bound or Scouting, The Game Loft also fosters risk-taking, leadership, and camarad erie. But for kids who find the football gridiron to be a foreign world, The Game Loft immerses them in a different sort of team sport.

Via table-top role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), Game Loft members play characters armed not with football padding and hockey sticks but chain mail, broadswords, light sabers, and magic spells. Working together, they charge onto battlefields and explore underground dungeons, seeking valor in these imaginary realms.

"I took to [role-playing] immediately," Delaney says. He joined as a member of The Game Loft, then started volunteering as a staff member, and finally became an employee. Along the way, the games he played built up his character in the real world.

"Killing dragons is a challenge," says Ray Esta brook, The Game Loft's codirector and cofounder. His center connects dragon-slaying to the challenges life throws at you. Via gaming, kids test out "roles," but in a safe, nonschool environment, in order to become functioning adults in society – connected, compassionate, and caring. "Good things happen to kids who game," he says.

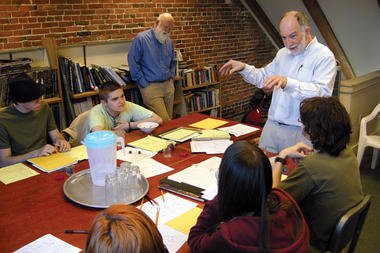

Cofounder Ray Estabrook (standing) leads gamers in playing '1968: Gone but Not Forgotten,' a game he and his wife and co-founder Patricia created.

Cofounder Ray Estabrook (standing) leads gamers in playing '1968: Gone but Not Forgotten,' a game he and his wife and co-founder Patricia created.

"I was [at The Game Loft] to socialize with kids who had mutual interest not only in games but conversation," Delaney says. "It was a place to channel a lot of curiosity." Moreover, he was able to interact with kids of all ages, as well as adults, who treated him as an equal. "The level of respect we got at The Game Loft was different than [at] school."

The Game Loft addresses another concern: the proliferation of video games. In an age when parents worry about the potentially isolating and addictive effects of computer and console-based games such as World of Warcraft and Halo, The Game Loft offers an antidote. No electronic games are allowed within its doors. Rather, kids play games

like D&D and Star Wars Miniatures face to face, with pencils and paper and plastic figurines, not with pixels and high-bandwidth Internet connections. A role-playing game is participatory, not passive. The kids don't absorb prefab plots from movies, books, or video games, but tell their own stories of their characters' exploits. Players around a

gaming table interact, completing quests and, yes, killing monsters who stand between them and their booty. In their imaginations, they are linked to humankind's narrativemaking past of heroic ballads and campfire tales of derring-do.

Each weekday at about 2 p.m., between 15 and 35 kids ages 6 to 18 (about one-quarter of them girls) break down the front door, pour up the stairs, and burst into The Game Loft's "Great Hall." The adjacent kitchen serves up hot food, sometimes the only nutritionally sound meal kids might get all day. They grab a brownie or bowl of chicken soup, separate into small groups (usually fewer than eight players) and head to the various rooms that host the game sessions. Once settled and fed, the kids quickly get down to the business of role-playing as elves and wizards, or plotting strategy as Jedi knights and military commanders.

But an unsupervised, free-for-all role-playing game can be just as cruel as a playground game of dodgeball. That's why game moderators like Tom Foster structure "intentional games" with outcomes that reinforce the center's principles such as fair play and cooperation.

In one room, called "The Savage Room" and decorated with maps and a suit of armor, Mr. Foster, who has been playing D&D since the 1970s, ran a multiweek, modified D&D game. He schooled his 12-to-15-year-old protégés in surviving the elaborate dungeon he'd designed and stocked with traps and monsters.

But when the adventuring party – "a group of misfits," as Foster affectionately called them – stepped on a tripwire, a cage opened that unleashed a bloodthirsty rhino.

Hands shot up, offering solutions. "I'm going to hide!" one girl shouted. "I've got an epic plan!" blurted another. "I want to jump on its back!" said another, whose character, inexplicably, took his clothes off and, via magic, turned invisible.

"Hold it, everyone! Focus," Foster said. "You've got a very large animal with three horns after you and you're arguing among yourselves." Eventually, they tricked the rhino into running into a vault and slammed the door. Success.

"Here, the idea is to get them from playing a game to solving problems," Foster later says. "To integrate."

Still, parents can be skeptical of the pedagogical goals. Some think their kids are just goofing off, says Kali Rocheleau, director of volunteers and membership. "But once we get them in the door, they have that 'aha' moment."

Sian Evans, whose two sons are Game Loft regulars, was one of those leery parents. She was no fan of video games, either, and wondered if fantasy games were too violent. But once she observed her sons in action, she noticed them begin to pass not only Pokémon cards back and forth across the gaming table, but also concepts.

"When you're playing D&D, you're talking about ideas," Ms. Evans says. "It's not games, it's life skills." She recalls a time that Taran, her 11-year-old, came home bubbling with enthusiasm about what had happened that day in the game: "Oh Mom, I got turned into a dwarf!"

"This is so special to him because he's active, he's part of the story," Evans says. "[Taran] would like to put a bunk bed in and live [at the Loft]."

The Game Loft's tools and settings aren't all fantasy. One custom-made game, 1968: Gone but Not Forgotten, re-creates life in a galaxy not so far, far away: Maine. "It's role-playing in an imaginary county, but touching on real history," says Patricia Estabrook.

"Our Maine history game is Dungeons & Dragons without the dungeons or the dragons," Ray Estabrook adds.

Games that let kids inhabit other selves from local history give them a stake in their own community. So do service projects that ask teens to take a break from battling orcs to give back. Townspeople see teens engaged in work like shoveling sidewalks for the elderly, not loitering downtown.

"It's important for youth to be involved in the community, not stuck behind some walled high school perimeter," Ray says.

For those at risk of dropping out of high school, The Game Loft can provide empowerment, accountability, and a way back in. Take Damion Saucier, 17, who felt oppressed by his school's educational system. "Me and school never clicked," Damion says. But at The Game Loft, he found "a big family," learned how to work with others, and also learned the necessity of obeying authority – sometimes. Now he's recommitted to school and volunteering as a game-session leader, teaching next-generation geeks. They look up to him. "You are like a god to them," he says. "It gives you a sense of helping these kids be social, and they're having fun."

The Game Loft has managed to turn the lingering "gaming is antisocial" stereotype on its head.

As for Max Delaney, just this March, after 11 years, he left his job at The Game Loft. The small-town kid moved to the faraway realm of Portland, Maine. He felt a little nervous, but also confident. After all, he knew how to role-play.

"We role-play in all situations in our life. It's unconscious," Delaney says. A job interview is really just role-playing, he notes, and games are a gateway to interaction. "We want to try to be someone else for just a little while, to experiment with it, to see who we can

be and what others are."

Like a character in a D&D game, who outfits himself before an adventure, then gains experience and grows in mastery, Delaney is well prepared for his next adventure – be it a job in social services, teaching, or wherever his quest may take him.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An

Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other

Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, which comes out in paperback in

September. Contact him through his website, www.ethangilsdorf.com