When is shock just schlock?

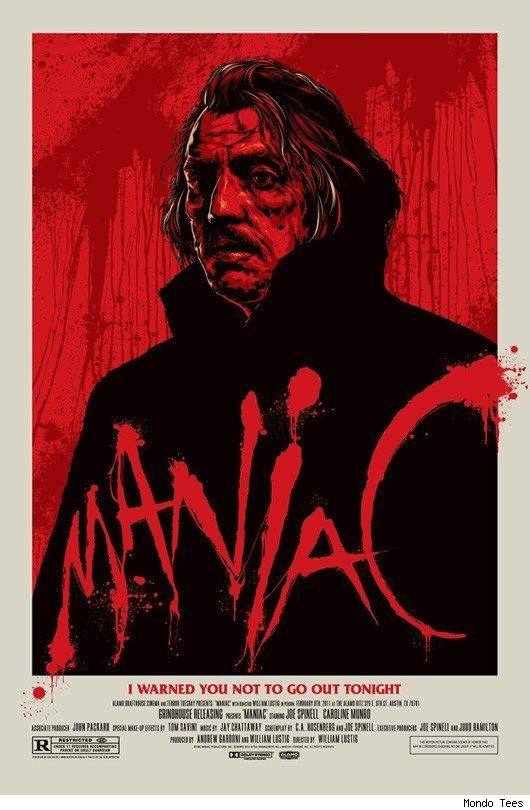

The re-release of William Lustig’s “Maniac’’ (1980), the notorious film in which a serial killer scalps women, is a chance to reevaluate shock value, or the value of shock, or schlock.

Ever since Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s 1929 “Un Chien Andalou’’ reinvented squeamish by showing a razor slicing open an eyeball, filmmakers have tested the limits of good taste. Whether in the service of high art or plain shock, films make us face what we’d rather not even imagine.

Each year ups the ante in some way. With gore galore, Tobe Hooper’s “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’’ (1974) reveled in being censored. William Lustig’s “Maniac’’ (1980) gave us a serial killer who scalps women. Peter Jackson’s “Meet the Feebles’’ (1989) depicted the lives of Muppet-like puppets not on Sesame Street but Skid Row. More gentle but no less revolting, the Farrelly brothers’ “There’s Something About Mary’’ (1998) suggested a new way to style Cameron Diaz’s hair. And so on.

Yet just because filmmakers can depict such depravities, should they? And how far can our envelopes be pushed before we, as an audience, feel ripped apart?

Yet just because filmmakers can depict such depravities, should they? And how far can our envelopes be pushed before we, as an audience, feel ripped apart?

Lustig has been appearing at theaters nationwide this winter to introduce a fresh, 30th-anniversary print of his notorious slasher film, and possibly address these and other questions. If nothing else, the re-release of “Maniac’’ lets us reevaluate shock value, or the value of shock, or schlock. [Upcoming dates include: February 18-19, Brookline, MA; March 11-12,Omaha Nebraska; March 26 & 27, Kansas City, Mo.; April 16th,

Richmond, VA; May 6, Phoenixville, PA; May 12, Stamford, CT; More info: http://www.grindhousereleasing.com/maniac.html]

In its day, Lustig’s film gained notoriety as among the most disturbing of its genre, not only because of the graphic violence — in one scene, a man’s head is shown blowing apart in slow motion — but because “Maniac’’ focuses on the killer, played by character actor Joe Spinell (“The Godfather,’’ “Taxi Driver,’’ “Rocky’’). Other horror movies like “Halloween’’ (1978) and “Friday the 13th’’ (1980) followed the victims. “You find yourself feeling empathy for someone committing despicable acts,’’ says Lustig in a phone interview from Los Angeles.

“Maniac’’ and its ilk helped usher in a new over-the-top horror category that attracted its share of controversy. Feminists protested the unrated “Maniac,’’ and “Sneak Previews’’ critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert incited audiences to boycott. “If ‘Maniac’ doesn’t deserve to be rated X for violence,’’ Siskel wrote, “no film does.’’ As for the rape-revenge flick “I Spit On Your Grave,’’ another poster-child slasher film, Ebert said “attending it was one of the most depressing experiences of my life.’’

Clearly, the moviegoer “finds pleasure in movies meant to challenge, disturb, shock and even sicken,’’ Newsweek critic David Ansen wrote. “But at what point does the challenging become the unbearable?’’ What inspired Ansen’s inquiry was the notorious 2002 French film “Irreversible,’’ which includes a 10-minute scene of Monica Bellucci being raped while her head gets pummeled against a cement wall.

If the point is to “push taboos,’’ says Lustig, a film like “Irreversible’’ succeeds. “There’s a liberation of ideas [in these films], a willingness to push the envelope, something that’s taboo.’’ Of course, gross-out stunts like drag queen Divine eating dog excrement in John Waters’s “Pink Flamingos’’ (1972) seem aimed only to induce a gag reflex. Other films, like Hitchcock’s “Psycho’’ (what Lustig calls “the granddaddy of them all’’), tapped into something more psychologically primal.

That we want and even need to have the bejesus scared out of us is clear; works by everyone from the Brothers Grimm to Stephen King have taught us that. If watching an action hero injects us with a shot of adrenaline, feeling disgusted by gore or repelled by torture reminds us of the limits — of morals, of pain, of our own bodies — we must not exceed.

Lustig never intended to sate any highfalutin cultural or psychic craving. “I made ‘Maniac’ as a horror film fan. I didn’t intellectualize it,’’ he says. “It wasn’t what I said, ‘to push the envelope.’ We just went on instinct. We were making the film for ourselves.’’ Lustig now heads Blue Underground, a DVD company that stokes our nostalgia for gore of yore, distributing lost classics about “psychopaths, cops, robbers, zombies, cannibals, madmen, strange women and more,’’ its website declares.

Undoubtedly, what it takes to shock us has changed since the Surrealist Twenties, the Comics Code Authority crackdown of the Fifties, and the Dungeons & Dragons/heavy metal parental freakout endured in the 1980s. Movies reset our boundaries, then we become habituated, then unimpressed.

“Years ago when we were younger, we craved some form of radical stimulation, and early horror/slasher films filled in the gap,’’ wrote Carl Cephas, president of Washington, D.C.’s Psychotronic Film Society, in a recent e-mail. But as visual stimulation “went into overkill,’’ the audience reached over-saturation. The films left nothing to the imagination. A new wave of film history twisted that border till it bled again.

Looking back, 1972 was a banner year for limit-pushing. Among other things it gave us “Pink Flamingos,’’ “Deliverance,’’ “The Last House on the Left,’’ and “Last Tango in Paris.’’ But even then, some suspected its alarming effect would prove ephemeral. Reviewing Bernardo Bertolucci’s “Last Tango,’’ Vincent Canby wrote, “It’s so Now, in fact, that you better see it quickly. I suspect that its ideas, as well as its ability to shock or, apparently, to arouse, will age quickly.’’

Or take 1975’s “Salò,’’ based on the Marquis de Sade’s book “120 Days of Sodom’’ but re-envisioned in Fascist Italy. Banned in its day, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film was available only as a bootleg until two years ago when it was finally released on DVD. But the long wait disappointed. “[People] were expecting gore, and they were bored,’’ says Brian “Horrorwitz’’ Horowitz, who runs a movie and collectibles business called Trash Palace out of Frederick, Md. We’d moved on.

Horowitz’s list of top audacious titles includes “Cannibal Holocaust’’ (1980), infamous because the director (Ruggero Deodato) was accused of making a snuff film; Sam Peckinpah’s 1971 “Straw Dogs,’’ known for its groundbreaking violence; and “A Clockwork Orange’’ (also 1971), which Stanley Kubrick pulled from theaters when it was accused of inciting gang violence. After each of these, more “more’’ became acceptable.

So what daring subject matter is left to colonize? And is it harder to make a more disturbing film these days when most boundaries have been explored, if not by mainstream movies then by video games and pornography? The answer might be the “torture porn’’ trend of the “Saw’’ series, or “The Human Centipede,’’ with its diabolical premise of a surgeon joining the digestive systems of three unfortunate tourists. Both are shocking, but also readable as responses to Abu Ghraib and our obsession with plastic surgery.

Meanwhile, recent remakes of “Last House,’’ “Texas Chainsaw,’’ and “I Spit on Your Grave’’ suggest the industry won’t take big risks. It wants to bank on the safety of familiar franchises, while soaking that cutting edge of what Canby called “Now’’ in as much blood as the ratings board can stomach. According to Cephas, it’s a game of “gore-upsmanship and the bucket is already full.’’

At least we’re beginning to look back on controversial films with rosier glasses. David Lynch’s 1977 “Eraserhead’’ was deemed by Variety a “sickening bad-taste exercise.’’ Now it’s a beloved cult film preserved by both the Library of Congress and National Film Registry. Same with “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,’’ now added to the permanent collection of New York City’s Museum of Modern Art.

As for Lustig, he went on to direct a few more films — “Vigilante’’ and the “Maniac Cop’’ series — but none attracted much controversy, or notice. Even though a “Maniac’’ remake is in the works, the slasher veteran seems jaded by the genre he helped to create. For him, better computer effects, more gallons of blood, is actually less. It’s what’s suggested in the mind, not splashed on the screen, that can disturb the most.

“I always thought that Steven Spielberg’s best film was ‘Jaws,’ ’’ Lustig says. “You have the shark that pops out of the water when Roy Scheider is chumming. But what sells it is the expression on Roy Scheider’s face. You see his veins popping out and see that fear. That’s what it’s all about.’’